Home >> Basic Concepts >> Assimilation

Assimilation

Index

- Introduction to Assimilation

- Classical Theories: The Chicago School

- Milton Gordon’s Multidimensional Model

- Critiques of the Assimilation Perspective

- Contemporary Debates and Cultural Politics

- Identity, Agency, and the Concept of Acculturation

- Assimilation in the Indian Context: Caste and Tribe

- Resistance, Stratification, and Urban Realities

- Conclusion

Introduction to Assimilation

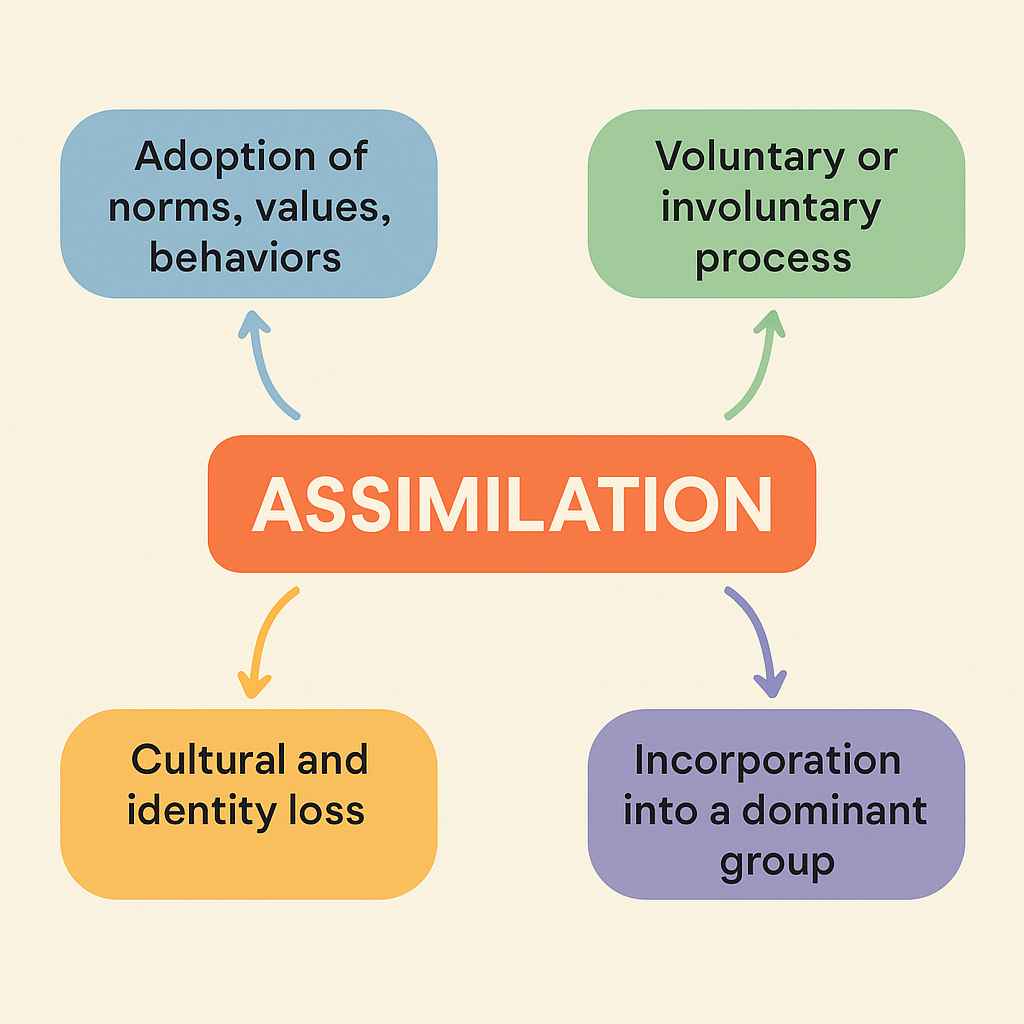

Assimilation is a foundational concept in sociology that refers to the process through which individuals or groups of differing ethnic, cultural, or social backgrounds come to adopt the norms, values, language, and behaviors of another—typically dominant—group. This process results in a gradual loss of the original cultural identity of the minority group as it becomes absorbed into the mainstream culture. The idea of assimilation is most commonly used in discussions about immigration, ethnic relations, and cultural integration, but it also applies broadly to any context where minority groups come into sustained contact with dominant groups. At its core, assimilation is about the reduction of cultural distinctiveness and the eventual incorporation of individuals or groups into a common cultural framework, often assumed to be “mainstream” or “national.” This process can be voluntary or involuntary, depending on the socio-political context.

Classical Theories: The Chicago School

From a theoretical standpoint, assimilation was first systematically studied by sociologists from the Chicago School in the early 20th century. Thinkers such as Robert E. Park and Ernest W. Burgess formulated the concept of the “race relations cycle” which includes four stages: contact, competition, accommodation, and assimilation. In this model, ethnic and racial groups come into contact, engage in conflict or competition, then reach a stage of adjustment, ultimately resulting in full assimilation into the host society’s culture. The Chicago School viewed assimilation as a linear and inevitable process of integration into urban industrial society. However, this approach has been critiqued for assuming a unidirectional process, where the minority must adjust to the dominant majority without reciprocal change or cultural negotiation.

Milton Gordon’s Multidimensional Model

Milton Gordon provided a more refined and complex understanding of assimilation in his influential work Assimilation in American Life (1964). He argued that assimilation is not a singular process but rather a series of distinct stages, each involving different dimensions of integration. Gordon identified several types of assimilation: cultural assimilation (adopting cultural patterns), structural assimilation (entry into social institutions), marital assimilation (intermarriage), identificational assimilation (shared identity), and civic assimilation (political integration). His theory helped to differentiate between superficial cultural adaptation and deeper institutional or structural integration. Importantly, he showed that a group could be culturally assimilated without enjoying full participation or equality within the dominant society.

Critiques of the Assimilation Perspective

Despite its theoretical richness, the assimilation model has been heavily criticized, particularly from postcolonial, feminist, and critical race perspectives. These critiques highlight how assimilation often masks coercive and exclusionary practices that demand conformity to dominant norms, usually shaped by colonial, patriarchal, or racial hierarchies. Rather than fostering genuine pluralism, assimilation may result in the erasure of minority cultures, languages, and traditions. It often reproduces power imbalances by presenting the dominant culture as normative and superior. In colonial contexts, for instance, indigenous peoples were often pressured to abandon their ways of life in favor of Western norms, creating a violent legacy of cultural dispossession.

Contemporary Debates and Cultural Politics

In modern multicultural societies, assimilation remains a deeply contested issue. In countries like the United States and France, political and cultural debates revolve around the extent to which immigrants and minorities should adopt national values or retain their distinct identities. While multiculturalism advocates for cultural pluralism, assimilationist policies often re-emerge in the form of civic nationalism, language requirements, and secularist agendas. For example, France’s strict secularism (laïcité) has led to bans on religious symbols like the hijab, which critics argue is a form of cultural suppression masquerading as national integration. In such contexts, assimilation becomes a site of cultural politics and state control rather than mutual integration.

Identity, Agency, and the Concept of Acculturation

Sociologists today recognize that assimilation is not always total or unidirectional. The concept of acculturation has been developed to describe processes where minority groups selectively adopt aspects of the dominant culture while retaining their own traditions. Similarly, segmented assimilation theory (Portes and Zhou, 1993) suggests that different groups assimilate into different segments of society—some into the mainstream middle class, others into marginalized or underprivileged sectors—depending on their social capital, racial background, and the host society’s receptivity. These approaches highlight the agency of minority communities and the non-linear nature of cultural change in diverse societies.

Assimilation in the Indian Context: Caste and Tribe

In India, assimilation takes on unique dimensions shaped by caste hierarchies, religious diversity, and tribal marginalization. The concept of Sanskritisation, introduced by M. N. Srinivas, can be viewed as a form of assimilation where lower castes imitate the customs and rituals of upper castes to gain social mobility. However, this often does not translate into real structural equality. Similarly, tribal groups have been subjected to assimilationist state policies under the banner of development or modernization. These include the imposition of mainstream education, displacement from ancestral lands, and forced adoption of dominant religious and social norms, leading to cultural alienation and identity crises among tribal populations.

Resistance, Stratification, and Urban Realities

Assimilation is not universally accepted or unopposed. Various groups resist assimilation through cultural revival movements, political activism, and identity assertion. For example, Dalit movements challenge the upper-caste-dominated framework and assert a distinct cultural and political identity rooted in Ambedkarite values. In urban India, the assimilation of internal migrants also reveals stratified experiences. Middle-class, English-speaking migrants may integrate easily, while rural or lower-caste migrants often face spatial segregation, cultural prejudice, and economic exclusion. These dynamics demonstrate that assimilation is shaped by structural inequalities related to class, caste, language, and gender, not merely by cultural willingness or adaptation.

Conclusion

Assimilation, as a sociological concept, continues to evolve and provoke critical questions about identity, integration, and equality in diverse societies. While classical theories emphasized cultural absorption and societal unity, modern perspectives expose the coercive dimensions of assimilation and advocate for more pluralistic and equitable forms of integration. The challenge lies in moving beyond assimilation as erasure toward models that allow for both inclusion and cultural distinctiveness. In an increasingly interconnected world, sociologists must grapple with the ethical, political, and human consequences of assimilation and envision frameworks that uphold dignity, diversity, and justice.

References

- Gordon, Milton M. Assimilation in American Life: The Role of Race, Religion and National Origins. Oxford University Press, 1964.

- Park, Robert E., and Ernest W. Burgess. Introduction to the Science of Sociology. University of Chicago Press, 1921.

- Srinivas, M. N. Social Change in Modern India. University of California Press, 1966.

- Portes, Alejandro, and Min Zhou. “The New Second Generation: Segmented Assimilation and Its Variants.” Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, vol. 530, 1993, pp. 74–96.

The term 'assimilation' again is in general use, being applied most often to the process whereby large numbers of migrants from Europe were absorbed into the American population during the 19th and the early part of the 20th century. The assimilation of immigrants was a dramatic and highly visible set of events and illustrates the process well. There are other types of assimilation, however, and there are aspects of the assimilation of European migrants that might be put in propositional form. First, assimilation is a two-way process. Second, assimilation of groups as well as individuals takes place. Third some assimilation probably occurs in all lasting interpersonal situations. Fourth, assimilation is often incomplete and creates adjustment problems for individuals. And, fifth, assimilation does not proceed equally rapidly and equally effectively in all inter-group situations.

Definitions:

- According to Young and Mack, Assimilation is the fusion or blending of two previously distinct groups into one.

- For Bogardus Assimilation is the social process whereby attitudes of many persons are united and thus develop into a united group.

- Biesanz describes Assimilation is the social process whereby individuals or groups come to share the same sentiments and goals.

- For Ogburh and Nimkoff; Assimilation is the process whereby individuals or groups once dissimilar become similar and identified in their interest and outlook.

Assimilation is a slow and a gradual process. It takes time. For example, immigrants take time to get assimilated with majority group. Assimilation is concerned with the absorption and incorporation of the culture by another.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|