Home » Social Thinkers » L.H Morgan

L.H Morgan

Index

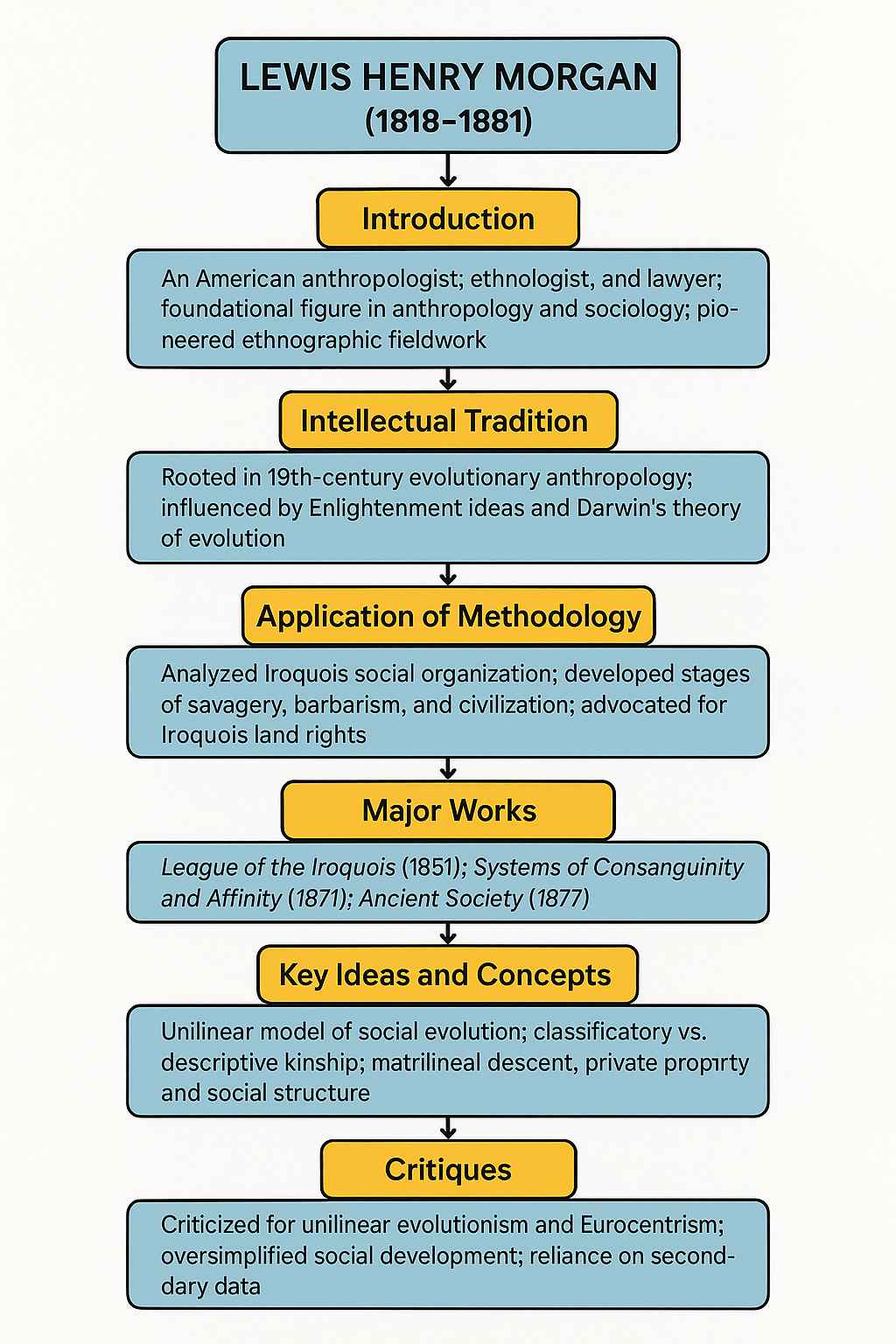

Introduction

Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881), an American anthropologist, ethnologist, and lawyer, is widely regarded as a foundational figure in the development of anthropology and sociology. Born in Aurora, New York, Morgan initially trained as a lawyer but became deeply interested in the study of Native American societies, particularly the Iroquois Confederacy. His fascination with their social organization, governance, and kinship systems led him to conduct pioneering ethnographic fieldwork, setting him apart as one of the earliest scholars to engage directly with the communities he studied. Morgan’s work laid the groundwork for systematic studies of kinship and social evolution, influencing not only anthropology but also sociology and related disciplines. His theories provided a framework for understanding human societies through a comparative and evolutionary lens, and his ideas on property and social organization resonated with thinkers like Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, who drew upon his work to develop theories of historical materialism. Morgan’s contributions, blending empirical research with theoretical innovation, established him as a pivotal figure in the scientific study of human societies.

Intellectual Tradition

Morgan’s intellectual contributions were firmly rooted in the 19th-century evolutionary school of anthropology, which was shaped by Enlightenment ideas of progress and the emerging influence of Charles Darwin’s theory of biological evolution. Alongside contemporaries like Edward Tylor and Herbert Spencer, Morgan applied evolutionary principles to the study of human societies, positing that all societies progressed through distinct stages of development. His work was informed by a positivist approach, emphasizing empirical observation, classification, and the search for universal laws governing social organization. Morgan’s comparative method involved analyzing diverse societies to identify common patterns, reflecting the intellectual climate of his time, which was marked by industrialization, colonialism, and a growing interest in understanding non-Western cultures. His correspondence with Marx and Engels highlights his engagement with broader social and economic theories, as his ideas about property and social evolution aligned with Marxist critiques of capitalism. This intellectual tradition positioned Morgan as a bridge between Enlightenment optimism about human progress and the emerging scientific study of culture and society.

Methodology

Morgan’s methodology was groundbreaking for its time, combining ethnographic fieldwork with comparative and historical analysis. His direct engagement with the Iroquois in New York set a precedent for immersive ethnographic research, as he lived among them, observed their customs, and documented their social and political structures. This hands-on approach was innovative in the 19th century, when much anthropological knowledge relied on second-hand accounts. To broaden his comparative framework, Morgan collected data on kinship systems from societies worldwide, including Native American tribes, Polynesians, and South Asian communities, using questionnaires distributed to missionaries, colonial administrators, and other informants. His evolutionary model categorized societies into three stages—savagery, barbarism, and civilization—based on technological advancements and social institutions, such as the development of agriculture or writing. Morgan’s methodology also involved systematic classification, particularly in his analysis of kinship systems, where he distinguished between “classificatory” systems (grouping relatives into broad categories) and “descriptive” systems (using specific terms for individual relationships). This rigorous approach aimed to uncover universal patterns in human social development, establishing Morgan as a pioneer in anthropological methodology.

Application of Methodology

Morgan’s methodology found practical expression in his extensive studies of kinship and social organization, most notably among the Iroquois and in his global comparative analyses. His first major work, League of the Ho-de-no-sau-nee or Iroquois (1851), applied ethnographic methods to document the Iroquois Confederacy’s matrilineal kinship, democratic governance, and communal organization, challenging Eurocentric stereotypes of Native American societies as “primitive.” In Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family (1871), Morgan employed his comparative method to analyze kinship terminologies across diverse cultures, using data collected through questionnaires to develop a typology of classificatory and descriptive systems. His magnum opus, Ancient Society (1877), synthesized his evolutionary framework, categorizing societies into stages of savagery, barbarism, and civilization based on technological and social advancements, such as the use of fire, agriculture, or legal systems. Beyond academia, Morgan’s methodology had practical implications, as he leveraged his findings to advocate for Iroquois land rights against colonial encroachments, demonstrating how his research bridged scholarship and social activism.

Major Works

Morgan’s major works form the cornerstone of his intellectual legacy and include League of the Ho-de-no-sau-nee or Iroquois (1851), Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family (1871), and Ancient Society (1877). League of the Iroquois provided a detailed ethnographic account of the Iroquois Confederacy, highlighting their sophisticated political structures, matrilineal kinship, and communal governance, which challenged prevailing stereotypes about indigenous societies. Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity was a groundbreaking comparative study of kinship systems across cultures, introducing the distinction between classificatory and descriptive terminologies and establishing Morgan as a pioneer in kinship studies. Ancient Society, his most influential work, outlined his theory of social evolution, proposing that all societies progress through the stages of savagery, barbarism, and civilization, with each stage marked by advancements in technology and social institutions. Additionally, Morgan published articles and delivered lectures on topics like Native American culture and material culture, further contributing to anthropological and sociological discourse.

Key Ideas and Concepts

Morgan’s key ideas revolve around his theories of social evolution and kinship systems, which have had a lasting impact on anthropology and sociology. His unilinear evolutionary model posited that all societies progress through three stages—savagery (hunter-gatherer societies), barbarism (agricultural societies), and civilization (societies with writing and complex institutions)—with each stage characterized by specific technological and social developments. Central to his work was the study of kinship systems, where he distinguished between classificatory kinship (grouping relatives into broad categories, e.g., calling all cousins “siblings”) and descriptive kinship (using specific terms for individual relationships, e.g., father, mother). Morgan argued that kinship systems reflect a society’s historical development and social structure. He also emphasized the significance of matrilineal descent, particularly among the Iroquois, where lineage and inheritance were traced through the mother, contrasting with patrilineal systems in Western societies. Morgan’s concept of the “gens” (a clan or kinship group) highlighted the democratic and egalitarian nature of pre-modern societies, while his linking of private property to the transition to civilization influenced Marxist theories of class and property.

Critiques

Despite his contributions, Morgan’s work has faced significant critiques, particularly for its unilinear evolutionary model and underlying assumptions. Critics, including later anthropologists like Franz Boas, argued that Morgan’s model oversimplified social development by assuming all societies followed a single trajectory, ignoring cultural diversity and historical contingencies. His use of terms like “savagery” and “barbarism” has been criticized for reflecting Eurocentric and colonial biases, portraying Western societies as the pinnacle of civilization. Morgan’s heavy emphasis on kinship as the primary determinant of social structure has also been seen as reductive, with later scholars highlighting the importance of other factors like economics, politics, and ideology. His reliance on secondary data, such as questionnaires from missionaries, led to inaccuracies in his global kinship studies, as some conclusions were speculative due to limited direct fieldwork. These critiques have shaped modern anthropology’s shift toward cultural relativism and more nuanced approaches to social change.

Contemporary Relevance

Morgan’s work remains relevant in contemporary anthropology, sociology, and related fields, despite the limitations of his evolutionary framework. His pioneering studies of kinship systems continue to inform ethnographic research, particularly in understanding family and social organization across cultures. His distinction between classificatory and descriptive kinship systems is still used in anthropological studies. Morgan’s influence on Marxist theory, particularly through Friedrich Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884), underscores his relevance in historical materialism and sociological critiques of capitalism. In indigenous studies, his detailed documentation of Iroquois society provides valuable insights into pre-colonial governance and social structures, supporting contemporary efforts to address indigenous land and cultural rights. Morgan’s work also serves as a historical reference for critiquing unilinear evolutionary models, informing debates on cultural relativism and postcolonial anthropology. His comparative approach and focus on material culture align with interdisciplinary studies of social change, technology, and globalization, ensuring that his contributions continue to resonate in modern social sciences.

References:

- Morgan, L. H. (1871). Systems of consanguinity and affinity of the human family. Smithsonian Institution.

- Morgan, L. H. (1877). Ancient society: Or, researches in the lines of human progress from savagery through barbarism to civilization. Henry Holt and Company

|

|

|

© 2025 sociologyguide |

|