Home >> Indian Thinkers >> A.R Desai

A.R. Desai in Indian Sociology: A Marxist Perspective

Index

|

|

1. Introduction: Life and Intellectual Formation

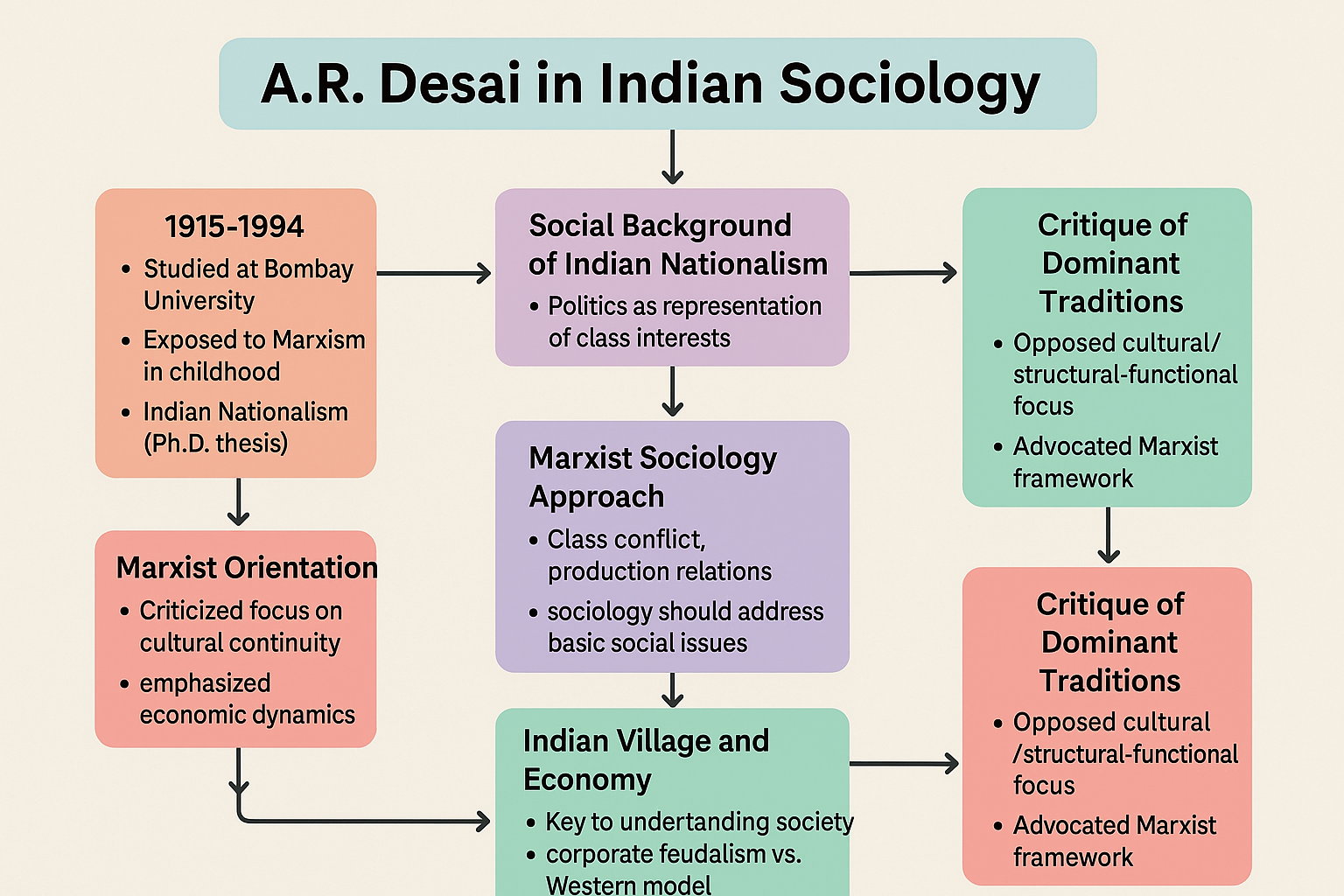

A.R. Desai (1915–1994) stands out as one of the most influential Marxist sociologists in India. Born in Baroda, he was exposed to Marxist ideas early in life through his father, who was himself a Marxist. His academic journey began at Bombay University, where he studied political philosophy and Indian culture under the guidance of the renowned sociologist G.S. Ghurye. Although Ghurye was a key figure in the cultural tradition of Indian sociology, Desai eventually departed from this orientation and pursued a Marxist framework. His Ph.D. thesis, titled The Social Background of Indian Nationalism, marked a significant departure from idealist or cultural explanations of nationalism and grounded the emergence of nationalist movements in material and economic conditions.

2. Marxist Orientation and Critique of Dominant Traditions

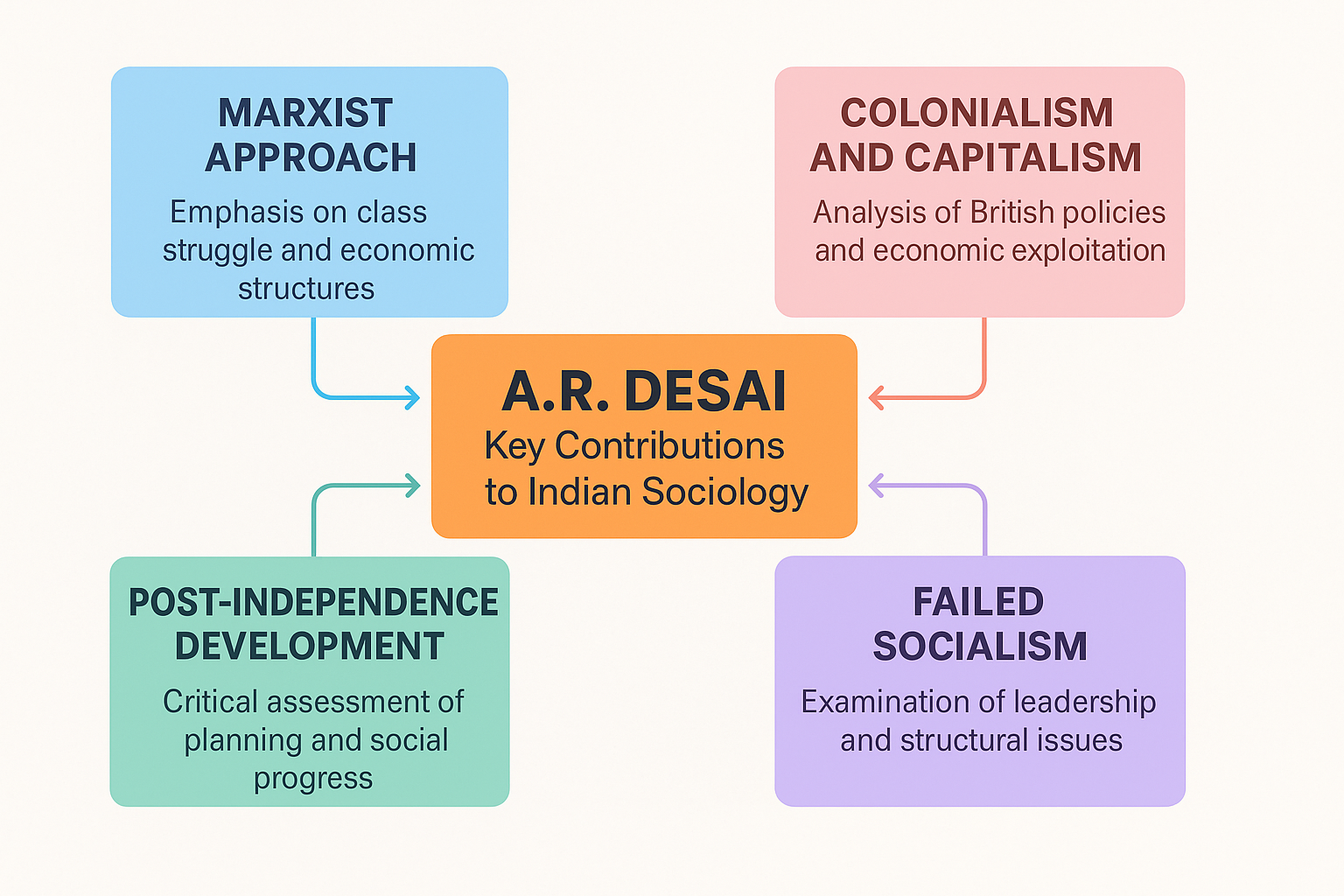

Desai was deeply critical of the dominant sociological traditions in India, particularly the cultural tradition represented by Ghurye and the structural-functional tradition led by M.N. Srinivas. While these approaches emphasized cultural continuity, tradition, and the functionality of social institutions, Desai found them lacking in their engagement with material conditions and economic structures. According to him, Indian sociology had become too focused on glorifying the past or analyzing institutions in isolation from economic dynamics. He believed the true concern of sociology should be to address the failure of development plans, rural distress, and the basic structural issues faced by Indian society, particularly farmers and laborers.

Desai proposed a Marxist alternative that emphasized class conflict, economic base, and production relations as central to understanding Indian society. He argued that any political or social movement must be understood as a reflection of the economic conflicts and class structure of that time. Thus, sociology, in his view, should serve as a tool for uncovering the ideological and economic underpinnings of social life, rather than merely describing cultural practices.

3. Sociology of Nationalism: Politics as Class Expression

Desai’s most celebrated work, Social Background of Indian Nationalism (1948), is a pioneering Marxist analysis of the Indian nationalist movement. Unlike nationalist historians who saw the movement as a product of spiritual awakening or moral leadership, Desai argued that nationalism in India arose due to the transformation in economic structures under colonial rule. The emergence of new classes such as the bourgeoisie, working class, and rural peasantry created conditions for the articulation of political consciousness.

In this framework, politics is seen as the representation of class interests, and political ideologies are expressions of deeper economic realities. For example, the moderate phase of nationalism represented the interests of the Indian capitalist class, while later radical movements represented the disenchantment of workers and peasants. Desai thus transformed the study of nationalism into a study of class-based political action.

4. Development of Marxist Sociology in India

Though Desai was not the rst Marxist thinker in India, his contribution is considered qualitatively dierent and pioneering within sociology. Earlier Marxist thinkers, such as E.M.S. Namboodiripad (who also authored works like Primitive Communism to Socialism), focused on ideological writings or political theory. Desai, on the other hand, brought a systematic Marxist methodology into the discipline of sociology, applying it rigorously to Indian social realities.

Desai also criticized Indian universities for not embracing Marxist approaches due to ideological bias. Despite this marginalization, his work laid the foundation for future Marxist scholars and offered an alternative framework that could challenge the status quo in both academic and political thought.

5. Concept of Mode of Production in Indian Context

One of Desai’s major contributions was his analysis of modes of production in India. He

divided Indian society into three broad modes of production:

1. Feudal Mode – prevalent during pre-colonial India.

2. Capitalist Mode – introduced and developed under British colonial rule.

3. Socialist Mode – expected post-Independence but not realized; instead, India ended

up with a failed socialism, characterized by a lack of genuine transformation in the

relations of production.

Desai was particularly concerned about the stagnation of the Indian economy and the state’s inability to transition into a productive socialist system. He drew from Karl Marx’s analysis of the Asiatic Mode of Production but also critiqued it for its reliance on colonial accounts and its inability to grasp the nuances of Indian rural economy.

6. Indian Village and Village Economy: Critique of Stagnation Thesis

Desai extensively analyzed the Indian village economy to understand the base of Indian

society. He challenged the British colonial thesis, particularly those like Charles Metcalfe,

who romanticized Indian villages as “little republics”, self-sucient and unchanging. While

Desai acknowledged the autonomy of village communities, he argued that they were not

stagnant but operated within a feudal framework with class divisions and exploitation.

He noted that Indian villages were structured around three types of land – agricultural

land, pasture land, and forest land – all of which were managed by village committees.

These committees controlled the factors of production and distributed land based on

use-value rather than market value. Though these villages appeared autonomous, they were

embedded in feudal power relations, with kings and landlords extracting taxes and surplus

from producers

Desai emphasized that village artisans and peasants produced for subsistence and not for prot, reecting a use-value economy rather than one based on market exchange. However, the introduction of British capitalism disrupted this structure, as land became privatized, markets penetrated rural areas, and new class structures emerged.

7. Corporatist Feudalism vs. Manor System: A Unique Indian Model

Desai made a significant conceptual distinction between the corporate feudalism of India and the manorial feudalism of the West. In the manorial system, the landlord had complete control over land and labor, deciding what to produce and extracting surplus through coercive means. In contrast, in India’s corporate feudalism, the village community controlled the land and production collectively, and the king only received a portion as tax. Therefore, there was no sharp class antagonism or class conflict in the villages, and the community remained cohesive.

This analysis helped Desai argue that Indian feudalism was structurally different and must be understood through its own internal logic, rather than being compared directly with European models. The Indian economy, in his view, combined agrarian production with artisanal industry and village self-sufficiency, which was disrupted only with the advent of British capitalism.

8. Impact of British Colonialism and Capitalist Transformation

Desai argued that the British colonial intervention transformed India’s economy fundamentally. The East India Company, after conquering territory through military might, replaced the Indian economic base with a capitalist system. They introduced private property, monetized the economy, and created port cities to serve their trade interests. Goods were imported from Britain and sold at lower prices, leading to the collapse of local industries. This converted India into a dumping ground for British goods.

Importantly, Desai noted that earlier rulers in India had not altered the economic base, but the British systematically changed both the economic base and superstructure, reshaping Indian society through capitalist exploitation.

Colonial Transformation and the Capitalist Mode of Production

British Economic Interests

Desai argued that British colonialism introduced capitalist structures in India, but not to develop the country—it was to serve Britain’s own industrial needs. The British built railways, roads, and communication systems primarily to extract raw materials and ship them to Britain. These so-called “modernizing” infrastructures were actually tools of economic domination, reinforcing India’s role as a dependent colony in the global capitalist system.

Land Tenure and Agrarian Changes

One of the most damaging transformations was in land tenure. The British dismantled traditional village ownership systems and implemented the zamindari system through Permanent Settlement. This created a new class of landlords aligned with colonial power, while dispossessing peasants and intensifying rural exploitation. Communal resource control was replaced with private ownership, leading to widespread landlessness and indebtedness.

Trade and Currency Exploitation

British trade policies allowed their manufactured goods to enter India freely, while Indian producers faced heavy restrictions and taxes. Industries like tea plantations were dominated by British capital, and Indian currency was devalued to favor colonial trade. The indigenous economy was dismantled, turning India into a market for British goods and a raw material supplier.

Forest Policies and Resource Control

Desai also examined how colonial forest laws dispossessed tribal communities. Forests were divided into reserved, protected, and village forests, all under state control. This limited the tribal population’s access to traditional livelihood resources, pushing them toward wage labor and deepening economic dependence.

Social and Demographic Consequences

These colonial policies disrupted India’s rural fabric. Increasing land pressure, rising tenancy, and loss of communal rights transformed India’s social character. Market-based production replaced subsistence economies, increasing inequality and weakening village solidarity. Desai saw these shifts as the groundwork for modern class antagonism.

Nationalism as an Economic Reaction

Desai viewed Indian nationalism not merely as a cultural awakening, but as an outcome of collective economic suffering under colonial rule. Exploitation by the British aected people across caste and religious lines, leading to a shared political consciousness. Nationalist leaders realized that political freedom had to be accompanied by a transformation of the economic system—especially production relations. Thus, the movement grew more radical in its vision, aiming to undo the structures of exploitation

Post-Independence Development: A Three-Decade Analysis

The Decade of Hope (1950s)

The rst decade after independence was marked by optimism. Under Nehru’s leadership, India adopted socialism and centralized planning as guiding principles. Desai appreciated this phase for its focus on welfare, inclusive development, and institution-building. Major initiatives like the Planning Commission, Five-Year Plans, and eorts to expand education and infrastructure reected genuine commitment to nation-building. Nehru aimed to reduce disparities by promoting human development and state-led industrialization.

The Decade of Despair (1960s)

However, after Nehru’s death, the momentum faltered. Promised benets failed to reach the masses. Industrial growth was uneven, unemployment rose, and food insecurity persisted. Literacy rates remained low, and land reforms were poorly implemented. Desai noted that social discontent grew as political parties failed to deliver on their developmental promises. People began losing trust in the system, and rural populations moved away from agriculture toward government jobs. Meanwhile, powerful landowners increasingly dominated politics, ensuring that land and wealth remained concentrated in a few hands.

The Decade of Discontent (1970s)

The 1970s brought systemic disillusionment. Desai pointed out alarming statistics: over 40% of Indians lived below the poverty line, 60% were still illiterate, and 80% of rural families were landless or nearly landless. Corruption in bureaucracy became widespread. Despite state claims of promoting entrepreneurship and extending facilities to rural areas, real benets were captured by elites. Tribal areas were especially exploited, with contractors taking control of natural resources and forcing tribal communities into construction labor. Exploitation of tribal women and displacement of indigenous livelihoods were common, intensifying anger and unrest.

Desai’s Critique of Failed Socialism

Leadership and Structural Gaps

Desai believed that India’s socialism failed because of poor leadership and the lack of structural reforms. Political independence did not result in redistribution of land or economic power. Leaders adopted the language of socialism but retained colonial economic structures. Instead of dismantling the exploitative system, they merely managed it under new political arrangements.

Key Issues of Concern

Desai’s framework questioned why land reform eorts stalled, why tribals became disillusioned (turning to movements like Naxalism), and why cooperative systems failed. He emphasized that recurring social disorders were rooted in unaddressed structural problems—particularly unequal access to land, education, and employment.

Need for Economic Restructuring

For Desai, real development required a complete restructuring of India’s social and economic systems. Without redistributing land, reforming agriculture, and expanding infrastructure to the marginalized, political freedom would remain hollow. He consistently called for a move beyond rhetoric to actual transformation of class relations and ownership structures.

9. Conclusion: Lasting Relevance of Desai’s Thought

A.R. Desai’s sociological contributions oer a powerful critique of both colonial exploitation and post-independence development failures. His Marxist analysis uncovered the continuities between colonial capitalism and India’s postcolonial political economy. Desai insisted that India’s future depended not on symbolic nationalism or electoral politics, but on confronting the economic foundations of inequality. His work remains vital for understanding why structural injustice persists, and what must be done to truly transform Indian society.

References

1. Desai, A.R. (1948). Social Background of Indian Nationalism

2. Desai, A.R. (1969). The Rural Sociology of India

3. Desai, A.R. (1989). India’s Path of Development: A Marxist Approach

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|