Home >> Indian Thinkers >> Gail Omvedt

Gail Omvedt

Index

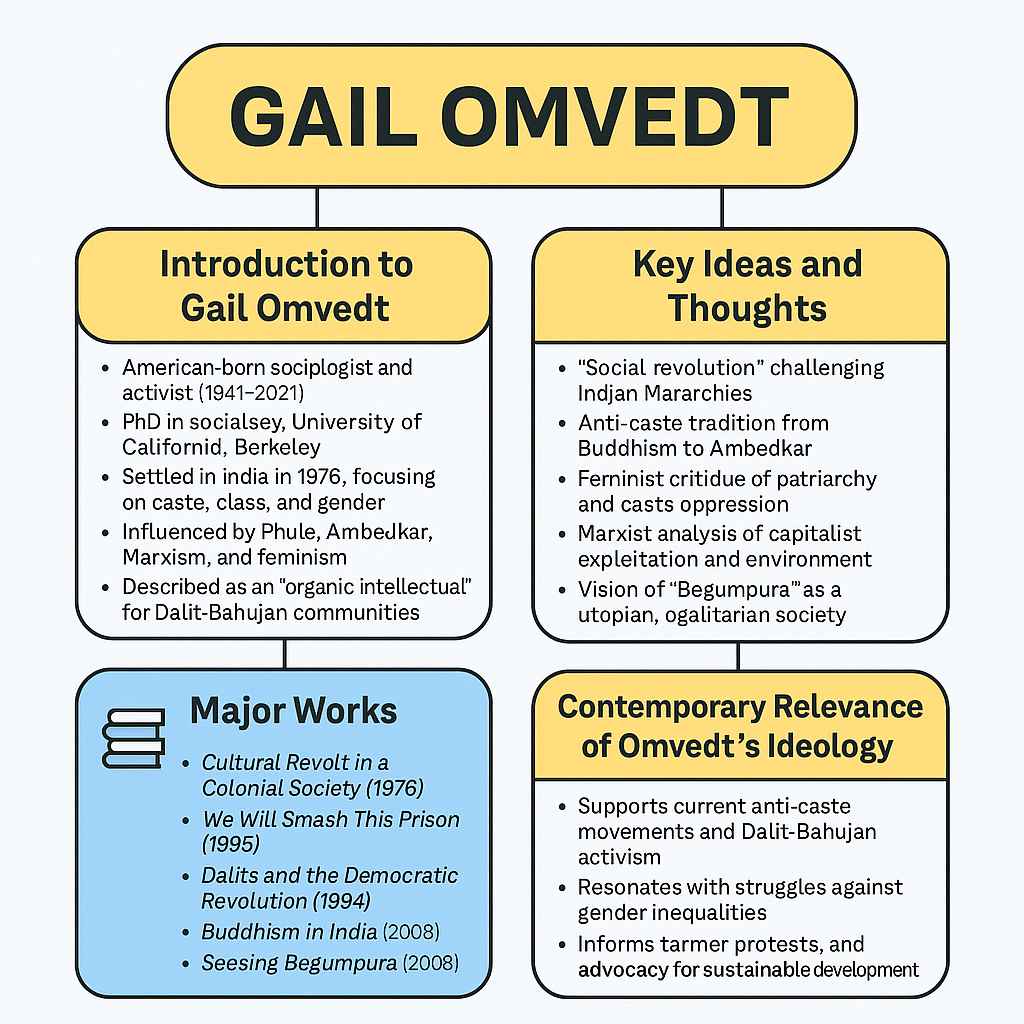

Introduction to Gail Omvedt

Gail Omvedt (1941–2021) stands as a towering figure in Indian sociology, renowned for her incisive scholarship and activism on caste, class, gender, and social movements. Originally from Minneapolis, USA, Omvedt earned her PhD in sociology from the University of California, Berkeley, and arrived in India in 1963 as a Fulbright tutor. Her decision to settle in India, marry social activist Bharat Patankar in 1976, and become an Indian citizen in 1983, rooted her in the social fabric of Kasegaon, Maharashtra. Omvedt’s work seamlessly blended academic rigor with grassroots engagement, focusing on the struggles of Dalits, women, peasants, and Adivasis. Infl uenced by anti-caste luminaries like Jyotirao Phule and B.R. Ambedkar, as well as Marxist and feminist frameworks, challenged the Brahmanical structures underpinning Indian society. Her dual role as a scholar and activist, described by Suraj Yengde as that of an “organic intellectual” of the Dalit-Bahujan community, amplifi ed the global visibility of India’s anti-caste movements. Omvedt’s scholarship not only enriched sociological discourse but also inspired transformative social action, making her an essential study for understanding India’s complex social dynamics.

Key Ideas and Thoughts

Omvedt’s intellectual contributions revolve around the intersections of caste, class, and gender, offering a radical critique of Indian society’s hierarchical structures. Central to her thought is the concept of a “social revolution,” distinct from the elite-led nationalist movements of the Indian Renaissance, as articulated in her 1971 article, “Jotirao Phule and the Ideology of Social Revolution in India.” She argued that Phule’s non-Brahman movement was a quest for social equality, not mere communalism, challenging the dominance of upper-caste narratives in Indian history. Omvedt traced an anti-caste intellectual tradition from ancient Buddhism through the Bhakti movement to Ambedkar’s Navayana Buddhism, proposing in Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste (2003) that India’s cultural identity could be reimagined as a “Buddhist India” to counter Brahmanical hegemony. Her feminist perspective, evident in We Will Smash This Prison (1980), highlighted the compounded oppression of Dalit and Bahujan women, whose economic and reproductive roles were central to her analysis of patriarchal and caste-based exploitation. Omvedt’s Marxist lens critiqued capitalist exploitation and environmental degradation, advocating for sustainable development and peasant-led movements to address resource inequities. Her vision of “Begumpura,” inspired by Bhakti poet Ravidas and elaborated in Seeking Begumpura (2008), envisioned a utopian society free from caste, class, and gender oppression, blending anti-caste, socialist, and feminist ideals into a cohesive framework for social justice.

Major Works

Omvedt’s prolific writings form a cornerstone of sociological studies on Indian social movements. Her doctoral dissertation, Cultural Revolt in a Colonial Society: The Non-Brahman Movement in Western India, 1873–1930 (1976), meticulously documented Jyotirao Phule’s Satyashodhak Samaj, analyzing its role in challenging Brahmanical dominance and laying the groundwork for anti-caste activism. We Will Smash This Prison: Indian Women in Struggle (1980) explored the intersection of caste and patriarchy, foregrounding rural women’s resistance and establishing Omvedt as a pioneering voice in Indian feminism. Dalits and the Democratic Revolution: Dr. Ambedkar and the Dalit Movement in Colonial India (1994) examined the evolution of Dalit movements from 1900 to 1930, analyzing their complex interactions with Gandhi, Marxists, and the nationalist struggle. Dalit Visions: The Anti-Caste Movement and Indian Cultural Identity (1995) offered a concise history of anti-caste struggles, from Phule to the Dalit Panthers, emphasizing their challenge to Hindu patriarchal structures. Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and Caste (2003) traced the anti-caste legacy from ancient Buddhism to Ambedkar, arguing for its revolutionary potential. Seeking Begumpura: The Social Vision of Anti-Caste Intellectuals (2008) synthesized the utopian aspirations of anti-caste thinkers, envisioning an egalitarian society. Additionally, Omvedt’s translations of Marathi works, such as Songs of Tukoba and Untouchable Saints, made Bahujan literature accessible globally, while her articles in Economic and Political Weekly provided nuanced analyses of caste, gender, and agrarian issues.

Critiques of Omvedt’s Work

Despite her profound contributions, Omvedt’s work faced critical scrutiny, refl ecting the complexity of her position as a scholar-activist. Some Indian academics initially marginalized her due to her non-traditional academic trajectory and her status as a white American scholar, which posed challenges to her acceptance within India’s academic establishment, even though her work was rigorously grounded in primary sources. Marxist critics, responding to her 1974 review essay in Journal of Contemporary Asia, argued that her emphasis on caste-specifi c struggles sometimes overshadowed class dynamics, potentially limiting the scope of her socialist critique in early works. Feminist scholars, while valuing her focus on rural and Dalit women, noted that Omvedt’s engagement with emerging concepts like intersectionality was limited, as her later work prioritized anti-caste and agrarian issues over nuanced gender theorizing. Her rejection of Hindu scriptures, such as the Rigveda, as promoting caste and conquest—articulated in her 2000 open letter in The Hindu—drew criticism from scholars who argued she over simplified Hindu cultural contributions. Additionally, some Dalit activists questioned her legitimacy as an outsider in identity-based movements, a concern Omvedt herself acknowledged when critiquing exclusionary defi nitions of movement membership based on caste. Nevertheless, her ability to globalize anti-caste thought and her commitment to grassroots activism earned her widespread respect, as affirmed by scholars like Suraj Yengde.

Contemporary Relevance of Omvedt’s Ideology

Omvedt’s ideas remain strikingly relevant in contemporary India, where caste, gender, and class inequalities continue to shape social and political landscapes. Her emphasis on anti-caste movements aligns with current demands for a caste census and policies to address systemic discrimination, reflecting the resurgence of Dalit-Bahujan activism she foresaw. Her documentation of Phule and Ambedkar’s legacies continues to inspire activists and scholars, as evidenced by tributes on platforms like X following her passing in 2021, which hailed her as a champion of the marginalized. Omvedt’s feminist insights, particularly her focus on Dalit and Bahujan women’s struggles, resonate with ongoing movements against gender-based violence and economic exclusion, as historian V. Geetha has noted. Her advocacy for eco-friendly development and peasant movements fi nds echo in recent farmer protests, such as those against India’s 2020 farm laws, which highlighted resource inequities she critiqued. Omvedt’s critique of Hindu nationalism as reinforcing caste hierarchies offers a framework for analyzing the rise of communal politics, making her work a vital lens for understanding contemporary challenges to secularism and equality. Her translations of Bhakti poetry and her global dissemination of Dalit literature continue to enrich cultural sociology, providing resources for studying India’s diverse identities. As Ramachandra Guha and Yashica Dutt have observed, Omvedt’s legacy as a scholar-activist endures, guiding both academic research and progressive movements toward a more equitable society.

References

Omvedt, G. (1971). Jotirao Phule and the ideology of social revolution in India. Economic & Political Weekly, 6(37), 1969–1980.

Omvedt, G. (1976). Cultural revolt in a colonial society: The non-Brahman movement in Western India, 1873–1930. Scientifi c Socialist Education Trust.

Omvedt, G. (1980). We will smash this prison: Indian women in struggle. Zed Press.

Omvedt, G. (1994). Dalits and the democratic revolution: Dr. Ambedkar and the Dalit movement in colonial India. Sage India.

Omvedt, G. (1995). Dalit visions: The anti-caste movement and Indian cultural identity. Orient Longman.

Omvedt, G. (2003). Buddhism in India: Challenging Brahmanism and caste. Sage India.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|