Home >> Indian Thinkers >> Radhakamal Mukherjee

Radhakamal Mukherjee

Index

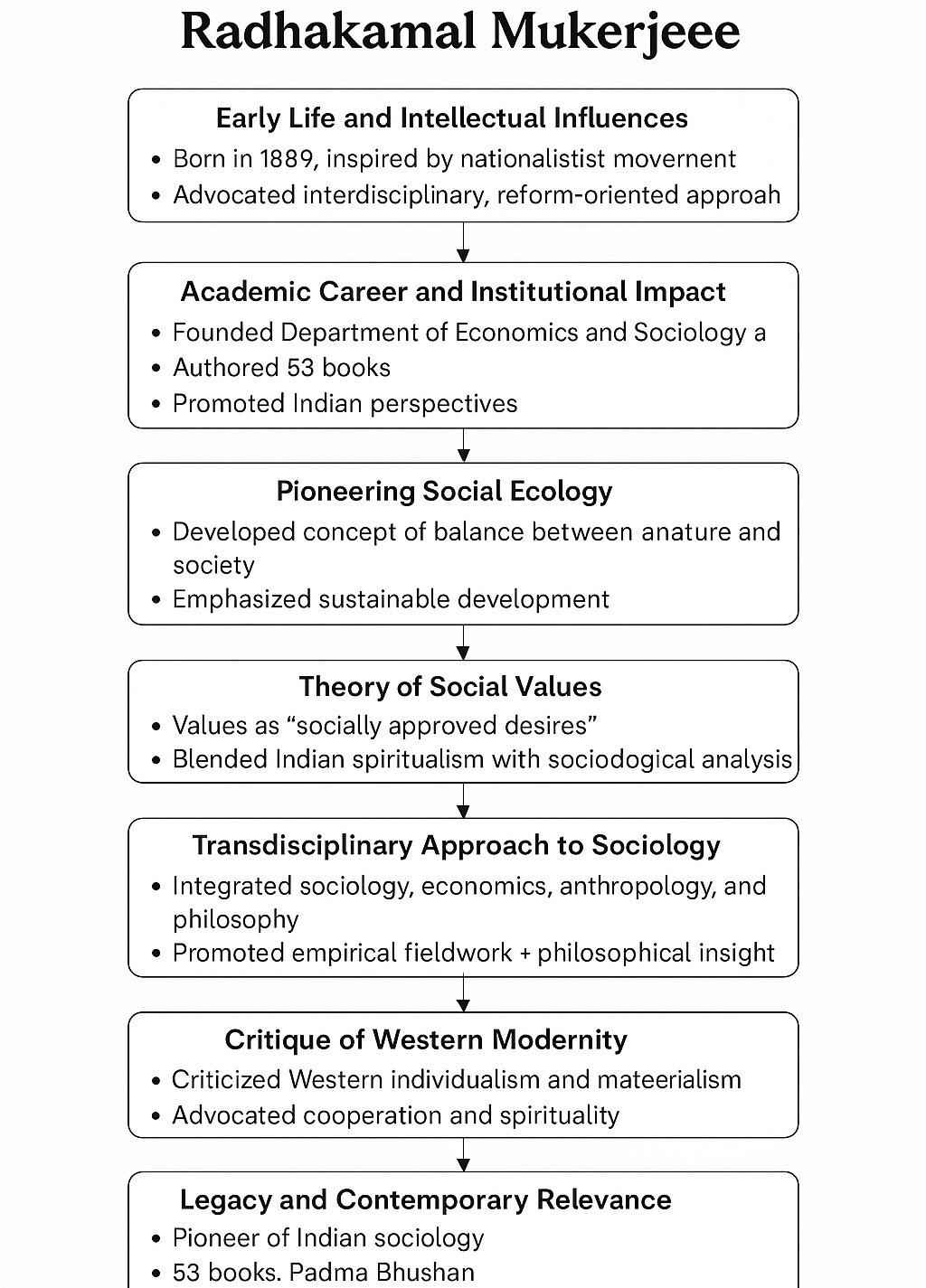

- Early Life and Intellectual Influences

- Academic Career and Institutional Impact

- Pioneering Social Ecology

- Theory of Social Values

- Transdisciplinary Approach to Sociology

- Critique of Western Modernity

- Contributions to Economic Sociology and Policy

- Critiques and Challenges

- Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Early Life and Intellectual Influences

Radhakamal Mukerjee (1889–1968) was a pioneering Indian sociologist, economist, and philosopher whose work profoundly shaped the development of social sciences in India. Born on December 7, 1889, in Berhampore, West Bengal, Mukerjee grew up in a scholarly household, the son of a barrister, with access to a rich library of history, literature, law, and Sanskrit texts. This environment nurtured his intellectual curiosity and interdisciplinary orientation. The early 20th-century nationalist movement, particularly the Swadeshi Movement following the 1905 partition of Bengal, ignited his patriotism and commitment to addressing India’s social and economic challenges. Mukerjee’s encounter with the plight of slum dwellers during this period deepened his interest in social reform, leading him to prioritize economics and sociology over his initial inclination toward history. He earned honors degrees in English and History from Presidency College, University of Calcutta, and later a PhD in 1920. His early career included teaching economics at Krishnanagar College (1910–1915), where he wrote foundational works like The Foundations of Indian Economics (1916) and edited the Bengali monthly Upasana. His involvement in adult education led to his brief arrest by British authorities in 1915 on charges of terrorism, reflecting his engagement with anti-colonial efforts. Influenced by thinkers like Brajendra Nath Seal, who lectured on comparative sociology, and Patrick Geddes, an urban planner critical of empire, Mukerjee developed a transdisciplinary approach that integrated sociology, economics, and ecology.

Academic Career and Institutional Impact

Mukerjee’s academic career was marked by significant institutional contributions, particularly at the University of Lucknow, where he became the first Chair of the Department of Economics and Sociology in 1921. He served as Professor and later Vice-Chancellor until 1952, establishing Lucknow as a leading center for social science studies in India alongside colleagues D.P. Mukerji and D.N. Majumdar, oen referred to as the “Lucknow triumvirate.” His interdisciplinary vision shaped the department’s curriculum, emphasizing the integration of sociology, economics, and anthropology. Mukerjee’s prolific output included around 53 books, covering topics from social ecology to economic sociology and cultural theory. He also played a prominent role in national and international academic circles, serving as Chairman of the Economics and Statistics Commission of the FAO in Copenhagen (1946), a member of the Indian delegation to the World Food Council in Washington (1947), and on various committees for the Government of Uttar Pradesh and the Union Government. His establishment of the Lucknow School of Sociology fostered a critical engagement with Western modernity, advocating for an Indian perspective in social science research. Mukerjee’s mentorship influenced generations of scholars, and his legacy is commemorated through awards and research centers dedicated to social ecology and sustainable development.

Transdisciplinary Approach to Sociology

Mukerjee’s sociological approach was distinctly transdisciplinary, integrating sociology, economics, philosophy, and anthropology to understand social phenomena holistically. He rejected the compartmentalization of Western social sciences, which he argued ignored “the lives and life-values” of non-Western societies. Inspired by American institutionalists like Thorstein Veblen and historical sociologists like Werner Sombart, Mukerjee conducted micro-level studies on rural economies, land issues (1926, 1927), population dynamics (1938), and the Indian working class (1945). His work during the Great Depression included inquiries into agrarian distress in Oudh (1929), setting a precedent for later agrarian studies. Mukerjee’s philosophical anthropology viewed the individual, society, and values as an “indivisible unity,” a concept he explored in works like The Dynamics of Morals (1951). He advocated empirical fieldwork alongside theoretical rigor, encouraging sociologists to ground their research in concrete evidence while considering historical and cultural contexts. This transdisciplinary vision positioned him as a pioneer in Indian social science, challenging Eurocentric paradigms and fostering an indigenous sociology

Critique of Western Modernity

Mukerjee’s sociology was deeply rooted in a critique of Western modernity, particularly its emphasis on individualism and industrialism. He argued that British-style social science neglected the collective and spiritual dimensions of Indian society, focusing instead on Darwinian competition and material progress. In works like The Institutional Theory of Economics (1940), he rejected the “blind adoption of Western industrial methods” in India, advocating for economic systems based on mutual cooperation and the Indian concept of sangh (collectivity), which prioritizes spiritual over materialistic values. Mukerjee’s critique extended to Marxist theories, which he saw as overly focused on class conflict and universal historical trajectories. Instead, he proposed a universalistic sociology grounded in Indian traditions, emphasizing cooperation and ecological balance. His concept of “Indianness” sought to legitimize Indian cultural and economic systems against colonial devaluation, contributing to the intellectual underpinnings of the Indian independence movement. This critique remains relevant for postcolonial sociology, which continues to challenge Western-centric frameworks.

Contributions to Economic Sociology and Policy

Mukerjee’s work in economic sociology bridged theoretical and practical concerns, addressing issues like rural economies, population dynamics, and labor conditions. His early writings, such as The Foundations of Indian Economics (1916), examined the economic structures of Indian villages, including communal resources like irrigation channels and mutual aid systems. During the 1920s, he conducted micro-level studies on agrarian distress, particularly in Oudh, highlighting the impact of colonial policies on peasantry. His later works, such as The Indian Working Class (1945), analyzed labor conditions, advocating for policies that balanced economic growth with social welfare. Mukerjee’s involvement in government committees, including those on family planning and forestry, reflected his commitment to applying sociological insights to policy-making. His emphasis on decentralized industries and diversified agriculture influenced early Indian planning, aligning with his vision of sustainable development rooted in ecological and social harmony.

Critiques and Challenges

Despite his pioneering contributions, Mukerjee’s work faced criticism for its perceived idealism and lack of theoretical rigor. Some scholars, like T.N. Madan, argued that his philosophical orientation, while profound, had limited impact on Indian sociology due to the dominance of Western empirical paradigms. Critics noted that his focus on values and ecology sometimes overlooked power dynamics and class conflicts, which Marxist sociologists like A.R. Desai emphasized. His universalistic vision was also seen as overly ambitious, potentially diluting the specificity of Indian social realities. Additionally, Mukerjee’s reliance on Indian mysticism and spiritualism was critiqued for romanticizing tradition, potentially sidelining the material struggles of marginalized groups. Nevertheless, his transdisciplinary approach and critique of Western modernity have been re-evaluated in recent years, particularly in environmental and postcolonial studies, where his ideas resonate with contemporary concerns about sustainability and cultural identity.

Legacy and Contemporary Relevance

Radhakamal Mukerjee’s legacy as a founding father of Indian sociology endures through his innovative contributions to social ecology, value theory, and transdisciplinary research. His establishment of the Lucknow School, alongside D.P. Mukerji and D.N. Majumdar, created a lasting intellectual hub for Indian social sciences. His 53 books, covering topics from ecology to cultural theory, reflect a prolific career that bridged Eastern and Western thought. Mukerjee’s emphasis on ecological balance and social values has influenced fields like environmental sociology, ecological economics, and sustainable development. His critique of Western modernity inspired postcolonial scholars to reassert indigenous perspectives in social science. Recognized with the Padma Bhushan in 1962, Mukerjee’s ideas remain relevant for addressing contemporary challenges like environmental degradation, urbanization, and cultural erosion. His call for a universalistic yet context-specific sociology continues to inspire researchers seeking to understand the complex interplay of society, culture, and environment in India and beyond.

References

- Mukerjee, R. (1916). The Foundations of Indian Economics. Longmans, Green & Co.

- Mukerjee, R. (1926). Regional Sociology. Calcutta University Press.

- Mukerjee, R. (1940). The Institutional Theory of Economics. Macmillan.

- Mukerjee, R. (1942). Social Ecology. Macmillan.

- Mukerjee, R. (1945). The Indian Working Class. Hind Kitabs Ltd

- Mukerjee, R. (1949). The Social Structure of Values. Macmillan

In his teachings and writings Mukherjee emphasized the need for mutual interaction between social sciences on the one hand and between social sciences and physical sciences on the other. Indian economics modeled on British economics mostly neglected the traditional caste networks in indigenous business, handicrafts and banking. Economic development was viewed as an extension of monetary economics or market phenomenon. The Western model in economics focused on the urban-industrial centers.

In a country like India where many economic transactions take place within the framework of caste or tribe, the market model has a limited relevance. He tried to show the relationship between traditional networks and economic exchange. The guilds and castes of India were operating in a non-competitive system. The rules of economic exchange were derived from the normative Hinduism in other words according to the norms of Hindu religion wherein interdependence between groups was emphasized hence to understand rural India the economic values should be analyzed with reference to social norms. Religious and ethical constraints have always lent a direction to economic exchange. Values enter into the daily life of people and compel them to act in collectively sanctioned ways.

Radhakamal Mukherjee wrote number of books on social ecology. For him social ecology was a complex formulation in which a number of social sciences interacted. The geological, geographical and biological factors worked together to produce an ecological zone. In its turn ecology is conditioned by social, economic or political factors. In the past many Indian ecological regions were opened up for human settlement and agrarian development through political conquests. As there is definite link between ecology and society the development of ecological zones must be seen in terms of a dynamic process that is challenge of the environment and response of the people who establish a settlement. Ecological balance is not mechanical carving out of a territory and settling people thereon. Such an attempt weakens or destroys social fabric. In his works on social ecology Mukherjee took a point of departure from the western social scientists. Social ecology was the better alternative to the havoc caused by rapid industrialization. India with its long history was a storehouse of values. Therefore in building a new India the planning must not be confined to immediate and concrete problems but must be directed towards value-based development.

Radhakamal Mukherjee wrote extensively on the danger of deforestation. The cutting of trees subjects the soil to the fury of floods and reduces the fertility of soil. The topsoil that is washed away by floods or excess rainfall cannot be replenished. Therefore the forests and woods of India were an ecological asset. He also referred to the danger of mono crop that is raising a single cash crop to the detriment of rotation of crops. Such practices as deforestation and mono cultivation disturbed the fragile ecosystem and gave rise to severe environmental problems. He advocated the integration of village, town and nation into a single broad-based developmental process. Urban development at the expense of the village should be kept in check. Agriculture should be diversified and industries decentralized.

Radhakamal Mukherjee had a sustained interest in the impact of values on human society. He held that a separation between fact and value was arbitrary. The facts and values could not be separated from each other in human interactions. Even a simple transaction was a value based or normatively conditioned behavior. Each society has a distinctive culture and its values and norms guide the behavior. Therefore the positivic tradition of the west that wanted to separate facts from values was not tenable to him especially in the study of a society like India. In the west there was a compelling need to free scientific enquiry form the hold of church theology. He underlined two basic points- values are not limited only to religion or ethics. Economics, politics and law also give rise to values. Human needs are transformed into social values and are internalized in the minds of members of society. Older civilizations such as India and China were stable. Hence values were formed and organized into a hierarchy of higher and lower fields. Values are not a product of subjective or individualistic aspirations. They are objectively grounded in humankind's social aspirations and desires. Values are both general and objective: - measurable by empirical methods.

Radhakamal Mukherjee's general theory of society sought to explain the values of a universal civilization. He used the term civilization in an inclusive sense culture was part of it. He proposed that human civilization should be studied on three inter-related levels – Biological evolution which has facilitated the rise and development of civilization. They have the capacity to change the environment as an active agent.

In psychosocial dimension the people are often depicted within the framework of race, ethnicity or nationhood. Human beings are seen as prisoners of little selves or egos whose attitude is parochial or ethnocentric. On the contrary human beings have the potentiality to overcome the narrow feelings and attain universalization that is to identify oneself with the larger collectivity such as one's nation or even as a member of the universe itself.

|

|

In his view the civilization has a spiritual dimension. Human beings are gradually scaling transcendental heights. They are moving up to the ladder of spirituality by overcoming the constraints of biogenic and existential levels. In this -art, myth and religion provide the impulsion or the force to move upward. Humankind's search for unity, wholeness and transcendence highlight the spirituality of civilization. He stated that human progress was possible only if glaring disparities of wealth and power between countries were reduced. So long as poverty persisted or political oppression continued further integral evolution of mankind was not a practical proposition. The persisting human awareness of misery in the world had stimulated the search for universal values and norms.

Some of the important works- The Regional balance of man (1938)

- Indian working class (1940)

- The social structure of values (1955)

- Philosophy of social sciences (1960)

- Flowering of Indian art (1964)

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|

Pioneering Social Ecology

One of Mukerjee’s most enduring contributions is his development of social ecology, a field he pioneered through works like Regional Sociology (1926) and Social Ecology (1942). He defined social ecology as “a synoptic study of the balance of plant, animal, and human communities, which are systems of correlated working parts in the organization of the region.” This framework emphasized the dynamic interplay between social structures, cultural practices, and ecological conditions, challenging the reductionist approaches of Western sociology. Mukerjee argued that geological, geographical, and biological factors interact with social, economic, and political forces to create ecological zones. He highlighted the consequences of disrupting ecological balance, such as deforestation leading to soil erosion, reduced rainfall, and loss of fertility, which he saw as detrimental to both the environment and social fabric. His ecological perspective was rooted in a critique of monoculture and over-urbanization, advocating for diversified agriculture and decentralized industries to maintain harmony between humans and nature. Mukerjee’s social ecology was groundbreaking for its time, anticipating modern environmental sociology and ecological economics, and remains relevant for addressing contemporary issues like sustainable development.