Home >> Indian Thinkers >> Yogendra Singh

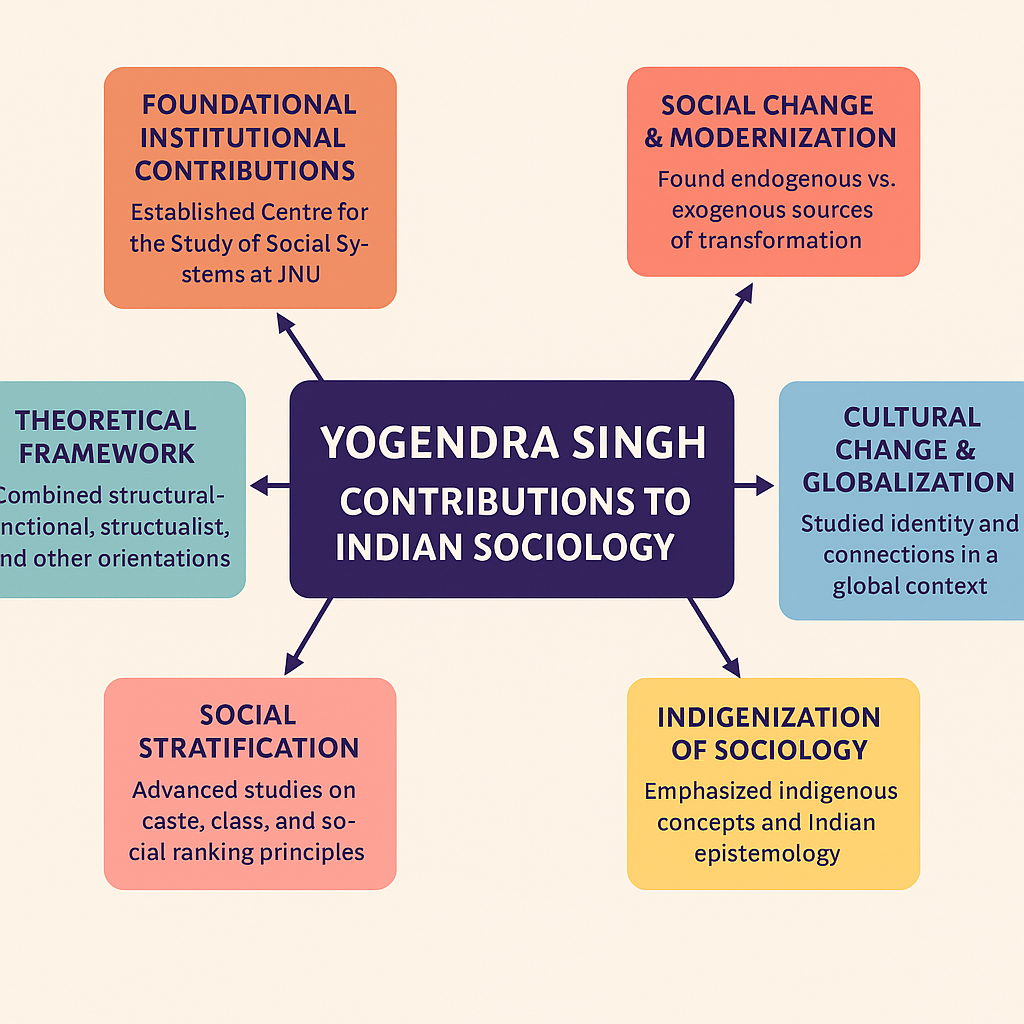

Yogendra Singh’s Contributions to Indian Sociology

Index

- Introduction

- Institutional Foundations

- Theoretical Framework and Methodological Pluralism

- Analysis of Social Stratification

- Theory of Social Change and Modernization

- Cultural Change and Globalization

- Indigenization of Indian Sociology

- Study of Contemporary Social Issues

- Philosophical Contributions to Sociology

- Conclusion

1. Institutional Foundations

Yogendra Singh was not only a prolific thinker but also a foundational institution builder who shaped the trajectory of Indian sociology through his academic leadership. He was the founder of the Centre for the Study of Social Systems (CSSS) at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi, in 1971, which soon became one of the most influential centers of sociological thought in South Asia. His vision for CSSS was to promote interdisciplinary and theoretically robust research grounded in Indian socio-historical realities. Singh began his academic journey at Lucknow University, where he was mentored by stalwarts like Radhakamal Mukerjee, D.P. Mukerji, and D.N. Majumdar. This early exposure to both empirical and philosophical traditions deeply shaped his sociological perspective. Later, at Rajasthan University, he helped establish a sociology department alongside T.K.N. Unnithan and Indra Deva, furthering the discipline’s reach in northern India. Throughout his career, Singh supervised more than thirty doctoral students, many of whom went on to become prominent sociologists. His institutional efforts ensured that sociology in India grew not merely as a derivative of Western theory, but as a dynamic field rooted in Indian experience and led by Indian scholars.

2. Theoretical Framework and Methodological Pluralism

Singh’s theoretical strength lay in his ability to integrate multiple sociological paradigms into a coherent framework suitable for the Indian context. Unlike some of his contemporaries who were rigidly attached to either functionalism or Marxism, Singh argued for what he termed a “methodological pluralism.” He brought together insights from structural-functionalism, historical materialism, structuralism, and culturalism, allowing for a more nuanced and multi-layered analysis of Indian society. His methodological innovations emphasized not just the “what” and “how” of sociological phenomena, but more importantly the “why” – calling for causal and critical understanding that could inform theory building. He consistently critiqued the uncritical transplantation of Western theoretical models into Indian sociology, arguing that such frameworks often ignored India’s unique historical and civilizational context. Singh insisted on the importance of historical specificity, cultural rootedness, and contextual relevance in sociological theorization. This led him to develop a deeply reflexive and grounded approach, through which he challenged the dominance of Eurocentric models and laid the foundation for an autonomous and indigenized Indian sociology.

4. Theory of Social Change and Modernization

Perhaps Singh’s most recognized contribution comes from his seminal work, “Modernization of Indian Tradition” (1973), where he developed an original theoretical model of social change in India. Departing from the dominant theories of sanskritization and westernization that shaped post-independence sociology, Singh proposed that Indian society undergoes modernization not through the simple replacement of tradition by modernity, but through a process of “structural selectivity.” According to Singh, traditional institutions like the joint family, caste, and religion adapt to modern values and selectively integrate them in a way that ensures their continuity in altered forms. His central thesis was that modernization in India is both exogenous and endogenous, shaped by colonial legacy, planned development, democratic polity, and cultural resistance. Singh defined modernization as a process of structural and cultural transformation, where changes in value systems, norms, institutions, and behavior lead to increased rationality, universality, and equality. However, this transformation is neither linear nor uniform. Singh emphasized that India’s experience of modernization is deeply context-dependent, involving conflict, adaptation, and hybridity, rather than wholesale imitation of Western institutions. This work marked a turning point in Indian sociology by placing modernization and tradition in a dialectical relationship, rather than treating them as binaries.

5. Cultural Change and Globalization

In the later decades of his career, Singh turned his attention to the profound effects of globalization on Indian culture, identity, and society. In “Culture Change in India: Identity and Globalization” (2000), he examined how global economic liberalization, technological change, and transnational media were reshaping Indian values, aspirations, and lifestyles. Singh explored the complex interaction between global and local forces, arguing that globalization does not lead to cultural homogenization, but rather intensifies cultural pluralism, hybridity, and identity negotiations. He analyzed phenomena such as the growth of consumer culture, diaspora consciousness, media-driven youth culture, and changing gender norms, and how these were transforming traditional cultural markers like caste, family, and religion. Singh was among the first Indian sociologists to recognize the emergence of cultural contradictions, where economic liberalization coexisted with cultural revivalism and identity politics. He demonstrated that while globalization expanded access to knowledge, opportunities, and diversity, it also led to new forms of alienation, commodification of values, and erasure of indigenous practices. His insights continue to be relevant in understanding the cultural dimensions of India’s post-1991 transformation.

6. Indigenization of Indian Sociology

A recurring theme in Singh’s work was the urgent need to indigenize Indian sociology without compromising its theoretical and methodological rigor. Singh was acutely aware of the “cognitive hiatus” that existed between Western theories and Indian social realities. He critiqued early Indian sociologists for adopting Eurocentric categories and assumptions, which often led to the misrepresentation or oversimplification of Indian social dynamics. Singh called for developing context-sensitive concepts, indigenous analytical frameworks, and historically grounded categories to ensure that Indian sociology could speak to both national and global audiences. His epistemological stance was not merely about rejecting the West, but about reconstructing sociology from within Indian civilizational knowledge systems. He also recognized that colonialism had shaped the very categories through which Indian society was studied, and that decolonizing Indian sociology involved rethinking not just content, but also disciplinary structure, pedagogy, and language. Singh’s call for indigenization was both methodological and ideological—a push toward a sociology that could explain, critique, and transform Indian society from within.

8. Philosophical Contributions to Sociology

Yogendra Singh also made important contributions to sociological theory and philosophy, especially in relation to the ideological foundations of sociological knowledge. In his writings on “ideology and theory”, Singh emphasized that no theory is value-neutral, and that the production of knowledge in sociology is influenced by worldviews, ethics, historical positioning, and disciplinary ideologies. He explored what he called the “images of man” in different sociological traditions—whether as a rational actor, a cultural being, or a bearer of class interest—and how these conceptions shaped sociological theorizing. Singh was a reflexive sociologist, urging others to be aware of their theoretical choices, positionalities, and disciplinary assumptions. He emphasized that Indian sociology must not only be empirical and analytical but also self-critical and ethically engaged. His work contributed to building a sociology of knowledge in India that interrogates how historical, institutional, and ideological forces shape the very act of sociological inquiry.

References

1. Singh, Yogendra. 1973. Modernization of Indian Tradition: A Systemic Study of Social Change. Delhi: Thomson Press India Ltd.

2. Singh, Yogendra. 1977. Social Stratification and Change in India. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers.

3. Singh, Yogendra. 1986. Indian Sociology: Social Conditioning and Emerging Concerns. New Delhi: Vistaar Publications.

4. Singh, Yogendra. 2000. Culture Change in India: Identity and Globalization. Jaipur and New Delhi: Rawat Publications.

|

|

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|

3. Analysis of Social Stratification

One of Singh’s most significant intellectual contributions was in the area of social stratification, where he offered a departure from earlier frameworks that treated caste as an isolated and all-encompassing category. In his influential book, “Social Stratification and Change in India” (1977), Singh proposed that caste must be studied in dialectical relation to class, region, ethnicity, and gender. He argued that the traditional ritual hierarchy model of caste had become inadequate to explain the material and political inequalities in post-independence India. Instead, Singh called for an analytical shift toward understanding intersecting forms of stratification that produce structural contradictions. He emphasized the need for macro-sociological frameworks supported by empirical data, testable hypotheses, and comparative methodology to study social ranking systems in a diverse society like India. Singh critiqued post-independence stratification studies for being overly descriptive and failing to ask explanatory ‘why’ questions. Through his work, he exposed the contradictions of agrarian capitalism, political mobilization based on caste identity, and urban stratification, highlighting that Indian society was experiencing new forms of inequality that required re-theorization. His analysis laid the groundwork for future sociologists to examine caste not as a timeless cultural system but as a dynamic and evolving mode of power and resource distribution.