Home >> Indian Thinkers >> G.S Ghurye

G.S Ghurye

Index

|

|

1. Introduction

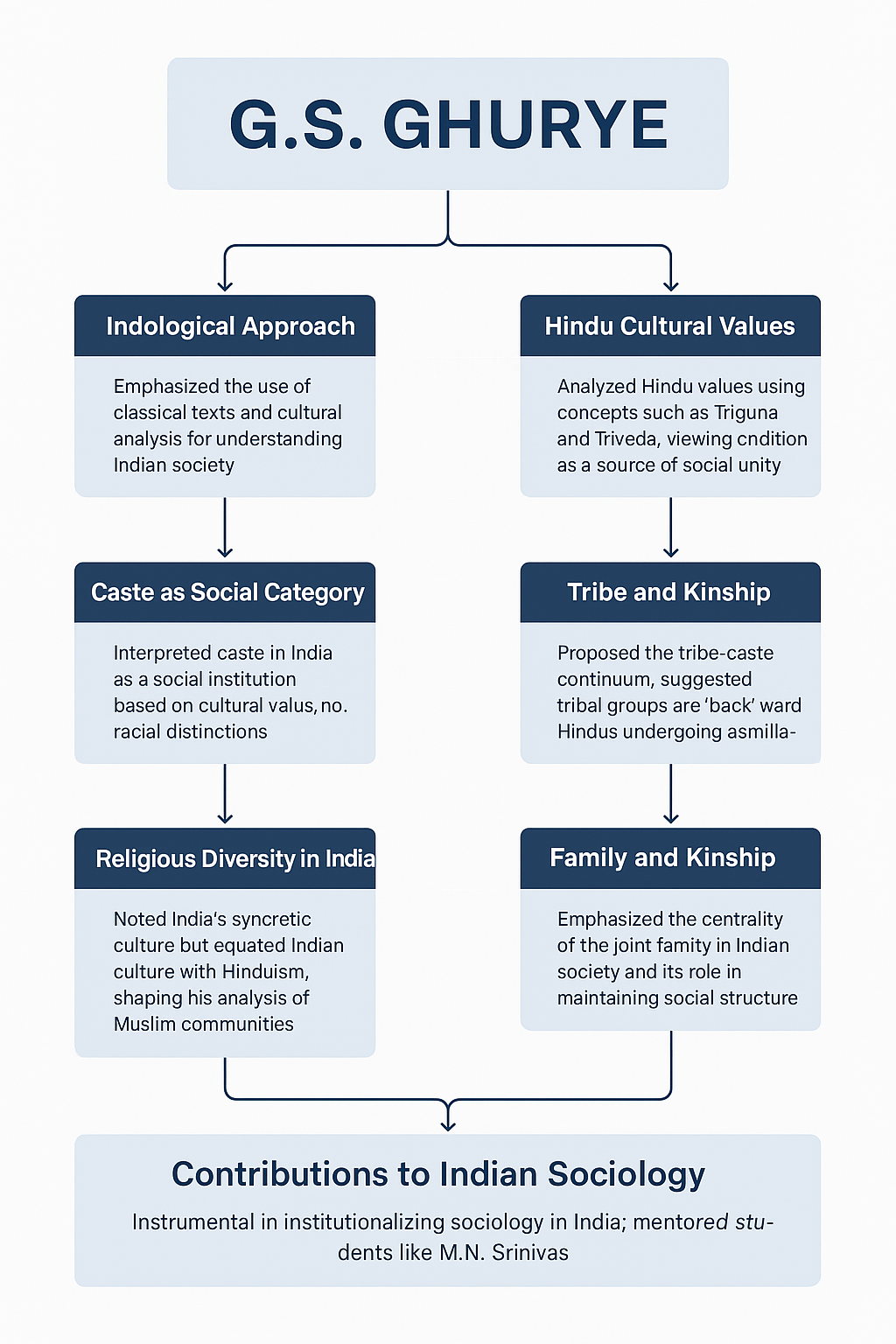

Govind Sadashiv Ghurye (1893–1983) is often hailed as the “Father of Indian Sociology.” His pioneering work laid the foundation for Indian sociology at a time when the eld was just emerging in India. Ghurye was one of the rst Indian scholars to provide a sociological lens to understand the complex socio-cultural fabric of Indian society. He blended Indological sources such as the Vedas, Smritis, Puranas, and Epics with contemporary social science theories, producing a uniquely Indian perspective on issues such as caste, race, tribes, family, and religion.2. Intellectual Background

Ghurye was born into an orthodox Brahmin family and received his early education at the Bhandarkar Institute. His keen interest in literature, particularly French and German, gave him an early exposure to European intellectual traditions. He opted for Sanskrit during college and completed his Master’s degree at Bombay University

A pivotal moment in his academic journey was his contact with Patrick Geddes, then Vice-Chancellor of Bombay University, who recognized Ghurye’s potential. Geddes encouraged him to pursue further studies abroad. Ghurye went on to study at the London School of Economics, where he briey interacted with philosopher Hobhouse and later trained in anthropology under W.H.R. Rivers at Cambridge. Although his direct engagement with Hobhouse did not bear much fruit, his training under Rivers left a deep impact on his methodological orientation, especially in ethnography and comparative studies.

Returning to India, Ghurye joined the newly formed Department of Sociology at Bombay University and led it for decades, mentoring over 150 students, publishing 45 books and over 200 articles. His long tenure helped institutionalize sociology as a formal academic discipline in India.

3. Ghurye’s Major Works and Key Themes

Hindu Cultural Values

One of Ghurye’s most consistent themes was his focus on Hindu cultural values. He approached Indian culture through a lens deeply embedded in Sanskritic traditions. In his view, Hindu values were not static or singular but were constituted through a rich interweaving of rituals, philosophical systems, mythology, and daily life practices.

He interpreted Hinduism using the concept of the “Triad” or Tridev — Brahma (creator), Vishnu (preserver), and Mahesh (destroyer). According to him, this triadic vision reected the Indian philosophical understanding of life as a cycle: every creation is destined for destruction, and destruction is necessary for renewal. These cosmological categories found sociological expression in the organization of Indian society and moral values.

He extended this further into the Triguna theory—Sattva (purity and knowledge), Rajas (action and passion), and Tamas (inertia and ignorance). He used this framework to explain social hierarchy: Brahmins, associated with Sattva, occupied the top of the caste hierarchy; Kshatriyas, linked with Rajas, came next; while groups associated with Tamas were placed at the bottom. This ideology, he argued, helped structure and justify social stratification in India.

The Concept of Unity in Diversity

Ghurye was one of the earliest scholars to argue that India’s unity was primarily ideological rather than political. He proposed that across its vast geography, India remained united through shared myths, religious traditions, epics, and values. It was not a unity imposed from above but one that emerged organically through the acceptance and internalization of Hindu values across diverse regions.

In his interpretation, the Triveda system (Rigveda, Samaveda, Atharvaveda) and the four ashramas (Brahmacharya, Grihastha, Vanaprastha, and Sanyasa) oered a life-course model that bound all Hindus in a shared worldview. He also emphasized the three Purusharthas—Dharma, Artha, and Moksha—as guiding goals of life. Ghurye claimed that such traditional value systems ensured continuity and a stable moral order.

This vision, however, was not without critique. Many have noted that his model of unity was rooted in Brahmanical values and did not adequately recognize the pluralistic and non-Hindu traditions in India.

Caste and Kinship in India

One of Ghurye’s most inuential works was his book Caste and Race in India, where he challenged the then-prevailing racial theories of caste. He argued that caste is not a racial category but a social institution rooted in ideology and cultural practice.

Ghurye held that the origin of caste lay not in birth, but in the division of labor based on the doctrine of karma and value orientation. He asserted that when Aryans migrated to India, they introduced the caste system, not as a racial tool but as a means of social organization, assigning occupations and responsibilities to groups based on their ethical and moral dispositions.

For Ghurye, caste was not inherently oppressive or divisive. He highlighted that caste provided stability by ensuring self-suciency and specialization. The endogamous nature of caste, along with kinship norms like gotra exogamy and sapinda rules, helped maintain social order. In his analysis, caste was also a cultural group with shared traditions and rituals, and its legitimacy stemmed from religious sanctions

While Ghurye’s analysis made important contributions, especially in refuting racial theories, it has been critiqued for underestimating the exploitative and hierarchical aspects of the caste system.

Tribe and Tribe-Caste Continuum

Ghurye made a signicant intervention in the study of tribes. He challenged the view that tribes were entirely separate from caste society, arguing instead that most Indian tribes were “backward Hindus.” He believed that tribes were not pre-social or isolated but were gradually being integrated into Hindu society through a process of Sanskritization.

He observed that tribal gods often resembled Hindu deities, and tribal myths could be absorbed into Hindu cosmology. This process of cultural diffusion led to the tribe-caste continuum, where tribal groups, through interaction with caste Hindus, gradually adopted Hindu customs and became part of the caste hierarchy. Ghurye highlighted examples of tribal chiefs marrying Hindu princesses or claiming Kshatriya status to legitimize their rule

However, this view has been heavily criticized for assuming Hindu superiority and for overlooking the autonomy and distinctiveness of tribal cultures. Moreover, his idea of voluntary assimilation has been questioned, especially in light of forced conversions, displacement, and state violence, particularly in the North-East.

Indian Muslims and Religious Coexistence

Ghurye also explored the position of Indian Muslims in his later writings. He noted that Indian Muslims came from diverse linguistic and ethnic backgrounds but were united by a common faith. He believed that Islam in India had undergone acculturation, and Muslim traditions, such as architecture, poetry, and court customs, significantly influenced Indian culture.

However, Ghurye expressed concern that the arrival of Muslim rulers led to the decline of Hindu values. He lamented the loss of Sanskrit’s significance, the closure of Hindu educational institutions, and the shift in political patronage. His tone, in these writings, sometimes bordered on Hindu nationalist nostalgia, leading to accusations of communal bias.

Despite this, he acknowledged that Indian society was a syncretic culture—not by force but through mutual accommodation. He accepted that Indian Muslims contributed richly to Indian civilization, even if he did not fully integrate this into his broader cultural model.

Indian Conception of Knowledge (Vidya)

One of Ghurye’s less discussed but intellectually rich contributions was his work on Indian epistemology. He contrasted traditional Indian knowledge systems with Western models. According to Ghurye, traditional knowledge (Vidya) was holistic, focusing on the formation of character and moral self rather than merely acquiring skills for the job market.

He argued that education in ancient India was deeply spiritual and value-laden. Gurus taught students not just texts but also humility, discipline, and the control of ego (Ahankar). The goal of knowledge was not power but self-realization. He was particularly critical of modern education, which he felt reduced knowledge to paper qualifications without ethical grounding

Ghurye’s approach here anticipated later debates on decolonizing education and valuing indigenous epistemologies.

4. Methodological Foundations

Ghurye’s methodology was rooted in Indology—the use of classical texts to understand Indian society. He combined this with empirical observations, creating a balance between textual and eld-based analysis. This dual method allowed him to develop a sociological imagination that was both historical and contemporary.

He was inspired by European classical sociologists but resisted their universalism. For Ghurye, Indian sociology had to emerge from Indian traditions, not as an imitation of Western theories. He considered tradition not as an obstacle but as a rich source of sociological insight.

This made him different from both Orientalist scholars and radical Marxists. His method was not without aws, however. Critics argue that textual sources like the Vedas reect elite, Brahminical views and cannot represent all of Indian society

5. Influence on Indian Sociology

Ghurye’s legacy is foundational. He institutionalized sociology in India by heading the Department of Sociology at Bombay University for over three decades. Many of his students—like M.N. Srinivas, A.R. Desai, and Irawati Karve—became leading sociologists themselves. He also founded India’s rst sociological journal, promoting indigenous scholarship.

More importantly, Ghurye established the Indological approach as a legitimate method in Indian sociology. While later sociologists like Srinivas adopted structural-functionalism, and Desai moved toward Marxism, all of them owed their intellectual beginnings to Ghurye’s academic mentorship and institutional vision.

6. Limitations and Criticisms

Despite his many contributions, Ghurye’s work has faced serious criticisms. First, his Hindu-centric framework has been called exclusionary. By equating Indian culture with Hinduism, he overlooked the pluralism of Indian society—especially the contributions of Muslims, Christians, Dalits, and Adivasis.

Second, his portrayal of caste as a stabilizing institution has been accused of romanticizing hierarchy. He underemphasized the exploitative and oppressive dimensions of caste, particularly for lower castes and Dalits.

Third, his understanding of tribes has been critiqued for its assimilationist bias. By calling tribes “backward Hindus,” he ignored their unique cultures and justified their absorption into Hindu society.

Fourth, Ghurye’s methodological reliance on texts often limited his sociological imagination. While rich in cultural analysis, his work sometimes lacked the empirical rigor demanded by modern sociology.

7. Conclusion

Govind Sadashiv Ghurye was a towering gure in Indian sociology. His work provided the rst indigenous framework to understand India’s complex social reality. Through his studies on caste, tribes, religion, kinship, and culture, Ghurye laid the groundwork for a uniquely Indian sociology—rooted in tradition, yet engaged with modernity. While his Brahmanical and nationalist biases cannot be ignored, they must be understood in the context of his time. His project was not merely to study Indian society, but to dene and defend its civilizational identity at a moment of colonial rupture.

References

1. Ghurye, G. S. (1932). Caste and Race in India.

2. Ghurye, G. S. (1943). The Scheduled Tribes.

3. Ghurye, G. S. (1950). Indian Sadhus.

4. Ghurye, G. S. (1955). Family and Kin in Indo-European Culture.

5. Ghurye, G. S. (1969). Social Tensions in India.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|