Home >> Indian Thinkers >> M. N. Srinivas

M. N. Srinivas

Introduction and Background

Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas (1916-1999) stands as one of the most inuential gures in Indian sociology, having established the sociology department at the Delhi School of Economics in 1959. His academic journey began with a PhD from Oxford University, where he encountered two pivotal intellectual inuences that would shape his entire scholarly career. Through Leonard Hobhouse, he absorbed liberal philosophical perspectives, while A.R. Radclie-Brown introduced him to structural functionalism and methodologies for studying small societies through intensive fieldwork

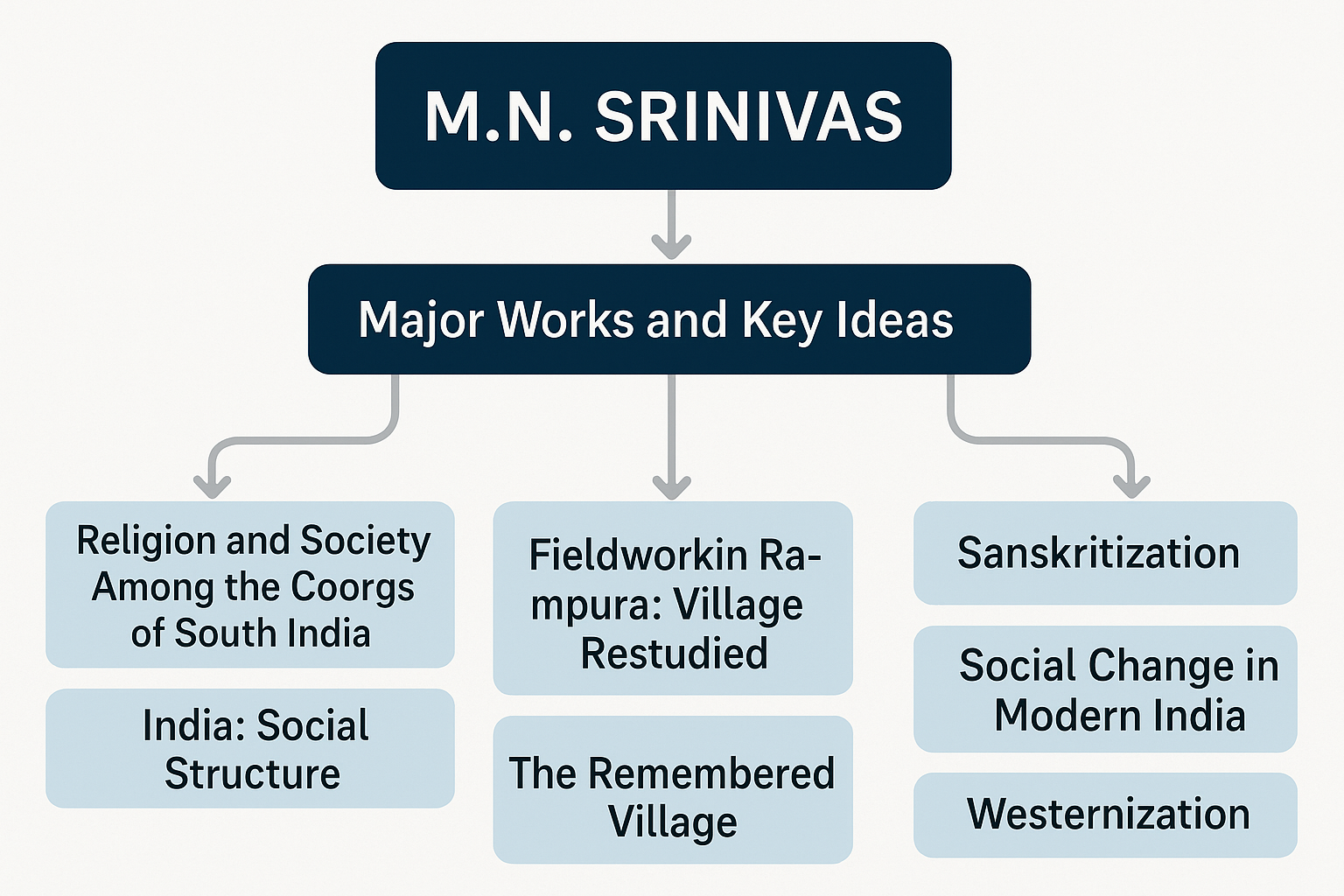

Srinivas’s doctoral research focused on “Society and Religion among Coorgs in Mysore,” which exemplied his commitment to grounded, empirical research. This early work established his reputation as a meticulous eldworker, culminating in his celebrated ethnographic study of Rampura village, documented in his seminal work “Remembered Village.” His scholarly contributions primarily centered on understanding caste systems, social stratication, and the dynamic processes of Sanskritization and Westernization in southern India. Perhaps most signicantly, he developed the inuential concept of “dominant caste,” which fundamentally altered how sociologists understood power structures in Indian villages.

The colonial period had created peculiar academic assumptions about Indian society being essentially unchanging and static. This led to an articial conjunction of Sanskrit studies with contemporary social issues in most South Asian departments globally, based on the belief that Indian sociology must necessarily bridge Indology and modern sociological analysis. Srinivas challenged these assumptions through his insistence on eldwork-based understanding rather than textual interpretation alone.

Theoretical Framework: Structural Functionalism

Srinivas was profoundly inuenced by British structural functionalism, particularly A.R. Radclie-Brown’s approach rather than the American variants developed by Parsons or Merton. This choice was deliberate and contextual—he argued that Parsonian structural functionalism was unsuited for a country like India, which retained numerous traditional elements alongside emerging modern structures. Brown’s theoretical framework proved more adaptable to the Indian context because it didn’t view structures as xed institutions but as products of evolving roles and relationships.

The structural functionalist perspective focuses on understanding the ‘ordering’ and ‘patterning’ of the social world, with particular attention to the ‘problem of order’ at societal levels. Followers of this approach generally assume that societies can be viewed as persistent, cohesive, stable, and generally integrated wholes, dierentiated primarily by their cultural and social structural arrangements. According to Srinivas, British social anthropology’s emphasis on structure and function implies that every society constitutes a whole, with its various parts being fundamentally interrelated. This meant that dierent groups and categories within society maintain complex relationships with each other.

Radclie-Brown provided three crucial concepts that Srinivas applied extensively in his Indian research: structural units (such as specic relationships like brother-sister bonds), structural forms (such as parent-child relationships or schools of classical dance), and structural morphology (such as the institution of family or the art form of Bharatanatyam). These analytical tools allowed Srinivas to examine Indian society’s complexity without imposing rigid theoretical frameworks that might distort empirical realities.

India’s social structure, as Srinivas observed, was neither entirely traditional (where every structure links systematically to every other structure) nor entirely modern (where structures are clearly dened and institutionally established). This intermediate character necessitated Brown’s more exible British sociological approach rather than the more rigid American variants. Srinivas demonstrated this through his analysis of Rampura village, where people transcended caste divisions to unite in protecting their common village pond from government intervention—illustrating dynamic structural adaptation.

|

|

Methodological Approach: Field View versus Book View

One of Srinivas’s most signicant contributions was his articulation of the distinction between “book view” and “eld view” approaches to understanding Indian society. The book view, also known as the Indological approach, derives knowledge about Indian social elements—religion, varna, caste, family, village structures, and geographical organization—primarily from sacred texts and scholarly literature. This perspective, while providing important historical and philosophical context, often presents idealized or normative accounts that may not correspond to lived social realities.

In contrast, the eld view emphasizes empirical research conducted through direct observation and participant involvement in actual communities. Srinivas believed that authentic knowledge about dierent regions of Indian society could only be obtained through systematic eldwork that engaged with people’s actual practices, beliefs, and social relationships. This approach led him to prefer small-scale regional studies over grand theoretical constructions, viewing eldwork as essential for understanding the authentic character of rural Indian society.

Srinivas strongly advocated ethnographic research based on participant observation, drawing inspiration from anthropological methods while adapting them to sociological inquiry. He argued against excessive reliance on jargon and elaborate theoretical designs, instead focusing on studying social reality outside the framework of grand theories. This approach brought sociology closer to social anthropology in the Indian context, which he considered appropriate since India’s social life was predominantly village-based, making anthropological methods particularly relevant.

Critics like Edmund Leach argued that outsider perspectives were important to prevent bias in social research. However, Srinivas countered that if sociological perspectives were clear and rigorous, analysis would necessarily be objective. Furthermore, he contended that insider researchers would be more sensitized to local nuances and could provide greater authenticity to research ndings. This methodological debate reected broader questions about objectivity, cultural understanding, and the relationship between researcher and subject in social science.

Understanding Caste: Beyond Western Assumptions

Srinivas’s analysis of caste fundamentally challenged Western scholarly assumptions that portrayed caste as a static system, contrasting it with supposedly dynamic class systems. Through his fieldwork, he discovered that caste was actually highly dynamic and underwent continuous changes over time. The book view of caste, driven by holistic textual interpretations, presented a fundamentally different picture from the eld view driven by empirical observation of actual caste practices and relationships.

His research revealed that the varna scheme—the four-fold theoretical division of society into Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras—was highly incomplete and failed to account for the enormous diversity of actual castes existing in Indian society. Conflicts emerged not only between different castes but also within caste groups, indicating internal diversity and complexity that theoretical frameworks often overlooked. Srinivas distinguished between varna and jati (actual caste groups), arguing that the varna scheme referred at most to broad social categories rather than actually existing, effective social units.

Relations between castes were governed by complex concepts of pollution and purity, with maximum commensality (inter-dining) typically occurring within caste boundaries. However, Srinivas noted that the varna scheme, while distorting the actual picture of caste relationships, had enabled ordinary people throughout India to understand and assess the general place of any caste within a common framework. This provided a shared social language that held meaning across different regions of India, creating familiarity and unity even when not based on accurate empirical facts.

Relations between castes were governed by complex concepts of pollution and purity, with maximum commensality (inter-dining) typically occurring within caste boundaries. However, Srinivas noted that the varna scheme, while distorting the actual picture of caste relationships, had enabled ordinary people throughout India to understand and assess the general place of any caste within a common framework. This provided a shared social language that held meaning across different regions of India, creating familiarity and unity even when not based on accurate empirical facts.

Sanskritization: Cultural Mobility within Traditional Framework

Srinivas’s concept of Sanskritization represents one of his most influential theoretical contributions to understanding social change in India. He defined Sanskritization as “the process by which a low Hindu caste or tribe or other group changes its customs, ritual, ideology and way of life in the direction of a high, and frequently twice-born caste.” This process involved lower castes adopting practices, beliefs, and lifestyles associated with higher castes, particularly Brahmins and Kshatriyas, in attempts to improve their social position.

The process typically involved aspiring groups adopting vegetarianism, teetotalism, and other practices associated with ritual purity. They would seek services of Brahmin priests, undertake pilgrimages to sacred centers, and acquire knowledge of sacred texts. Castes located in the middle of the stratication system particularly engaged in this mobility strategy by emulating upper-caste behaviors, ideologies, and rituals. In pursuing elevated status, these groups were required to abandon traditional practices considered polluting or inferior according to dominant caste ideology.

Sanskritization manifested in various forms throughout Indian history. Historically, it sometimes involved collective recognition of lower castes’ elevation to upper-caste ranks following acts of chivalry, economic advancement, or political alliances. Such mobility was often legitimized through consensus among dominant castes and formal recognition by kings or other authorities. This historical form had wider political and economic implications, though its impact was typically conned to specic regions or sub-regions

The more common contextual form involved unilateral attempts by castes or sub-castes to move upward in hierarchy without broader consensus. This form often met resistance from dominant castes and was seldom legitimized within existing caste structures. Most empirical cases of Sanskritization belonged to this category—slow, non-spectacular processes of cultural mobility lacking wider political implications but representing signicant eorts at social advancement within traditional frameworks.

Interestingly, Srinivas also identied processes of de-sanskritization and re-sanskritization. Some castes, like the Koris of eastern Uttar Pradesh, rejected twice-born superiority and refused to accept water from Brahmins, contributing to crystallization of new group identities and greater political mobilization. Re-sanskritization involved formerly westernized groups discarding symbols of modernization and reverting to traditional sanskritic lifestyles.

Westernization: Colonial Impact and Social Change

Srinivas defined Westernization as changes brought about in Indian society and culture through over 150 years of British rule, encompassing transformations at multiple levels including technology, institutions, ideology, and values. Unlike Sanskritization, which had affected Indian society for centuries, Westernization was a comparatively recent and largely urban phenomenon that ran in directions opposite to traditional mobility patterns.

British rule provided fresh avenues for social mobility by altering existing institutions and establishing new ones. Schools and colleges opened their doors to all castes, while new institutions like the army, bureaucracy, and law courts recruited members based on merit rather than traditional status, providing unprecedented opportunities for advancement. These changes fundamentally altered the landscape of social mobility in Indian society.

The process of Westernization didn’t begin and end with British rule but provided tracks that furthered and accelerated mobility processes. It initiated transformations that gained further momentum after Independence, as independent India inherited rationalistic, egalitarian, and humanitarian principles from British administration and created additional room for social mobility. This continuity between colonial and post-colonial periods demonstrated Westernization’s lasting impact on Indian social structures.

Both Sanskritization and Westernization operated primarily at cultural levels, involving adoption of different sets of practices, values, and lifestyles. However, they represented fundamentally different orientations—Sanskritization looked toward traditional high-caste models while Westernization embraced modern, rational, and egalitarian principles. The coexistence and sometimes conflict between these processes created complex dynamics in post-colonial Indian society.

Dominant Caste: Redening Village Power Structures

Srinivas’s concept of “dominant caste” revolutionized understanding of power relationships in Indian villages by demonstrating that ritual ranking no longer remained the major basis of social hierarchy. According to his formulation, a caste becomes dominant when it is numerically strongest in a village or local area and exercises preponderating economic and political influence. The status of dominant caste rests on multiple criteria: control of economic resources, numerical strength, relatively high ritual status, and educational achievement among members.

Numerical strength alone doesn’t guarantee dominance—it requires an economic power base for effective influence. However, once economic rights are secured, group size becomes significant in determining political outcomes. Control of resources by dominant caste members leads to decision-making authority over others, constituting real dominance in village affairs. This concept highlighted how economic and political factors had become increasingly important relative to traditional ritual considerations.

Numbers without unity don’t guarantee power, as numerically preponderant caste groups with divided loyalties may fail to wield effective influence. Only when caste groups achieve political unity do they become genuine political forces capable of influencing village decisions. This insight demonstrated the importance of social cohesion and political organization in converting potential demographic advantages into actual power

The dominant caste concept revealed how former lower castes had gained prominence through various reforms including Panchayati Raj institutions and land reforms. This created situations where ritual domination remained with Brahmins while secular domination shifted to previously backward castes, illustrating the changing nature of power relationships in post-independence India.

Social Change: Orthogenetic and Heterogenetic Processes

Srinivas identified two fundamental types of social change: orthogenetic changes originating from within Indian society (such as Buddhism and Jainism) and heterogenetic changes introduced from outside (such as British-type industries and institutions). This classification helped explain different patterns of social transformation throughout Indian history.

Based on these change processes, he identified three types of people representing different combinations of traditional and modern orientations: those experiencing internal Sanskritization with external Sanskritization, those undergoing internal Sanskritization with external Westernization, and those embracing internal Westernization with external Westernization—the last category being most numerous in contemporary India

In his later work, including “20th Century Avatar of Caste,” Srinivas noted how ideologically incompatible caste groups were increasingly coming together to capture political power, demonstrating pragmatic political calculations overriding traditional social boundaries. His nal lecture, titled “Obituary to Caste,” argued that caste appeared primarily where needed rather than dominating all aspects of social life as in the past, suggesting significant transformation in caste’s social role.

Gender Issues and Social Structure

Srinivas addressed gender issues within his broader analysis of Indian social structure, particularly focusing on dowry practices and women’s social positions. In his 1980s article “Some Reflections on Dowry,” he characterized dowry as “modern sati,” arguing that rapid economic transformation had led to commodification of women who were used as instruments for consolidating private wealth. He observed that contemporary caste society showed tendencies for cognate jatis to merge into single entities for marriage purposes, both imposing constraints and creating dominant ethos underlying dowry practices within Hindu society.

His analysis revealed that women’s social world was synonymous with household and kinship groups while men inhabited more heterogeneous environments. Masculine and feminine pursuits were clearly distinguished and hierarchically ordered, with women’s occupations considered not only separate but unequal. This gendered division of social space reflected broader patterns of inequality embedded in traditional social structures.

Family and Village Structures

Srinivas challenged conventional assumptions about Indian family and village structures through his empirical research. Regarding family organization, he argued that Indian society hadn’t simply transitioned from joint to nuclear families but rather moved from joint to “fission extended families”—a more complex pattern that maintained certain aspects of joint family organization while adapting to changing circumstances.

His analysis of village structure contested colonial notions of Indian villages as completely self-sufficient republics. Villages, he demonstrated, were always parts of wider entities rather than isolated units. Despite this external connectivity, villages maintained internal solidarity manifested during marriages, fairs, festivals, and disasters. Villages weren’t closed entities—their residents regularly interacted with outsiders while maintaining distinctive local identities.

Srinivas argued that individuals in his studied village maintained strong identification with their community, treating insults to the village as personal affronts equivalent to insults to family members. This sense of locality remained significant despite increasing urbanization, suggesting persistence of village-based identity even amid broader social changes.

Criticisms and Limitations

Srinivas’s work faced several significant criticisms that highlighted limitations in his approach and perspectives. He admitted to deliberate exclusion of Harijan wards during his data collection, approaching Dalits only through upper-caste headmen. This methodological choice resulted in accounts biased toward upper-caste Hindu perspectives, undermining claims to comprehensive village studies. Critics argued that while Srinivas discussed economic and technological development, he consistently sidetracked lower segments of society in these analyses. His promotion of Sanskritization as a mobility strategy was seen as marginalizing and alienating religious minorities who couldn’t participate in Hindu-centric improvement processes. His understanding of Indian traditions was criticized as exclusively Hindu-centered rather than genuinely secular, with concepts like Sanskritization and dominant caste appearing to align with Hindutva ideology of cultural nationalism.

Some scholars questioned the originality of his concepts, noting that what he characterized as Sanskritization had been previously described by proto-sociologists like Lyall and Risley as “Aryanization” and “Brahminization.” This suggested that his theoretical contributions involved repackaging existing observations in contemporary sociological terminology rather than discovering entirely new social processes.

Conclusion and Legacy

Despite criticisms, Srinivas occupies an eminent place among India’s rst-generation sociologists. His emphasis on “eld view” over “book view” represented a remarkable step toward understanding Indian social realities through empirical investigation rather than textual interpretation alone. This approach reected what might be called “sociology of nativity”—understanding society through direct engagement with local communities and practices.

His structural-functional analysis of communities like the Coorgs demonstrated complex interrelationships between ritual and social order while addressing crucial notions of purity and pollution. His work illuminated processes through which non-Hindu communities became incorporated into Hindu social orders, contributing to understanding of Sanskritization as a mechanism for cultural integration and mobility within traditional frameworks.

Srinivas’s concepts of Sanskritization, Westernization, and dominant caste provided analytical tools that remain relevant for understanding social change in contemporary India. While his work had limitations and biases, it established foundations for empirically-grounded Indian sociology that moved beyond colonial assumptions about static, unchanging traditional society. His legacy lies in demonstrating that Indian society, far from being rigid and unchanging, contained dynamic processes of adaptation, mobility, and transformation that could be understood through careful eldwork and analysis.

References

1. Srinivas, M. N. 1952. Religion and Society among the Coorgs of South India. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

2. Srinivas, M. N. 1976. The Remembered Village. Berkeley: University of California Press.

3. Srinivas, M. N. 1962. Caste in Modern India and Other Essays. Bombay: Asia Publishing House.

4. Srinivas, M. N. 1966. Social Change in Modern India. Berkeley: University of California Press.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|