Home >> Indian Thinkers >> Louis Dumont

Louis Dumont

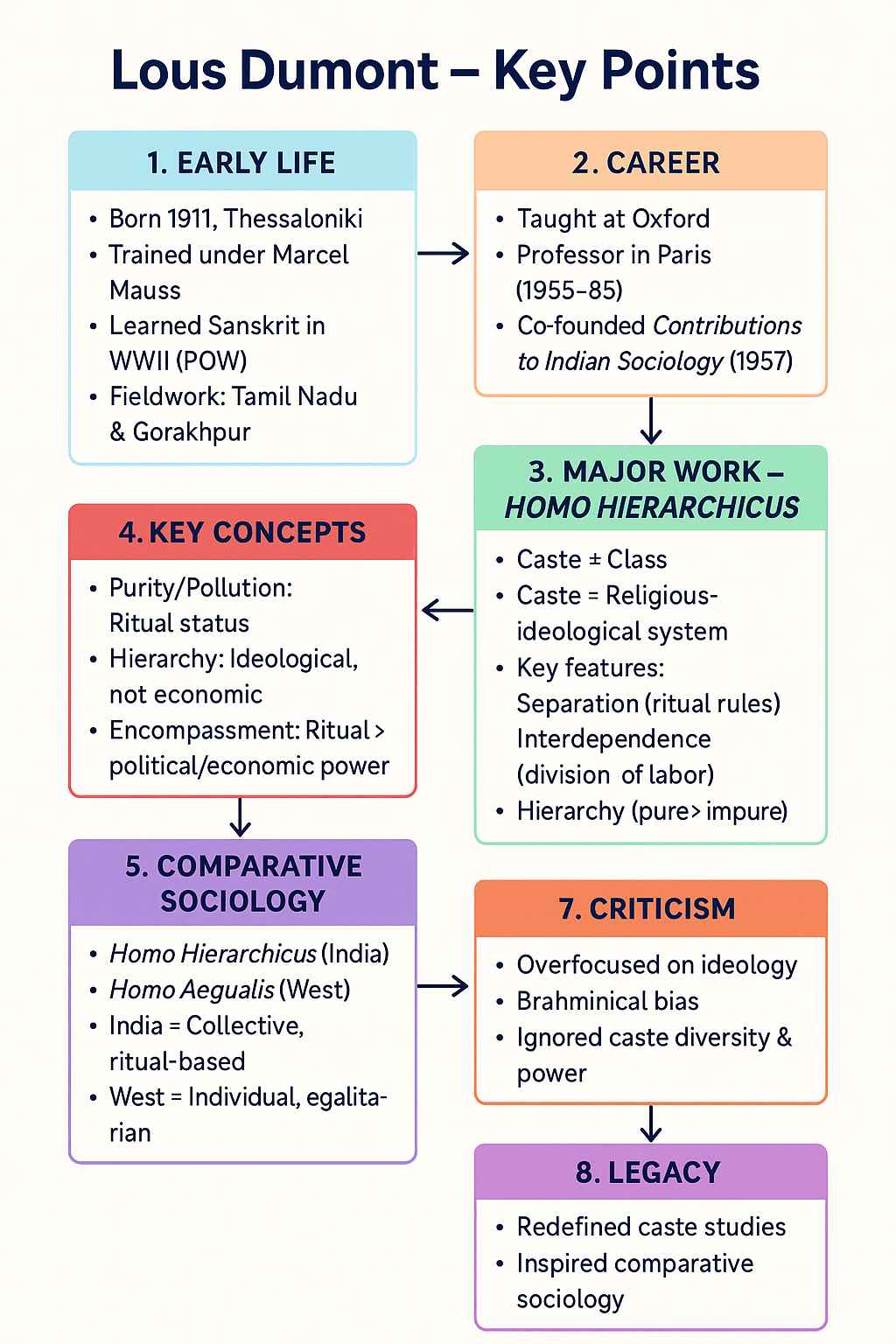

Index

- Early Life and Intellectual Formation

- Academic Career and Institutional Contributions

- Homo Hierarchicus: A Landmark in Sociology

- Key Concepts: Purity, Pollution, and Hierarchy

- Comparative Sociology: Homo Hierarchicus vs. Homo Aequalis

- Methodological Approach: Confluence of Indology and Sociology

- Critiques and Controversies

- Legacy and Influence

- Conclusion

|

|

Early Life and Intellectual Formation

Louis Dumont (1911–1998) was a French anthropologist, sociologist, and Indologist whose work le an indelible mark on the study of Indian society and comparative sociology. Born in Thessaloniki, then part of the Ottoman Empire’s Salonica Vilayet (modern-day Greece), Dumont grew up in a family that blended artistic and technical influences—his grandfather was a painter, and his father an engineer. This duality shaped his intellectual approach, fostering a creative imagination grounded in a focus on concrete social realities. His academic journey began in the 1930s at the Institute of Ethnology at the Musée de l’Homme in Paris, where he studied under Marcel Mauss, a towering figure in French sociology and anthropology known for his work on gi exchange and Sanskrit studies. Mauss’s influence introduced Dumont to structuralism and the comparative study of societies, laying the groundwork for his later theories. During World War II, Dumont’s studies were disrupted when he was captured and held as a prisoner of war in Germany from 1940 to 1945. There, he began learning Sanskrit under German Indologist Walther Schubring, an experience that ignited his lifelong fascination with Indian culture. Aer the war, Dumont conducted extensive fieldwork in India, first among the Pramalai Kallar in Tamil Nadu (1949–50) and later in a village in Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh (1957–58). These experiences, combined with his Indological training, positioned him uniquely to bridge textual analysis with ethnographic observation, a hallmark of his sociological approach.

Academic Career and Institutional Contributions

Dumont’s academic career was distinguished by prestigious appointments and institutional contributions that amplified his influence in sociology and anthropology. In the early 1950s, he served as a lecturer at Oxford University, succeeding Indian sociologist M.N. Srinivas, where he engaged with anthropological debates on kinship and social organization. In 1955, he was appointed a research professor at the École Pratique des Hautes Études in Paris (later École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales), where he remained until his retirement in 1985. This position allowed him to develop his theoretical framework and mentor generations of scholars. In 1957, Dumont co-founded the journal Contributions to Indian Sociology with British anthropologist David Pocock, creating a vital platform for advancing the sociological study of India. The journal emphasized interdisciplinary approaches, combining anthropology, sociology, and Indology, and became a cornerstone for scholars studying South Asian societies. Dumont’s institutional roles and his commitment to fostering dialogue between Western and Indian intellectual traditions solidified his reputation as a leading figure in comparative sociology, though his work oen sparked debate for its bold generalizations.

Homo Hierarchicus: A Landmark in Sociology

Dumont’s most influential work, Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications (published in French in 1966, with English translations in 1970 and 1972), is a seminal contribution to the sociology of India and comparative social theory. The book offers a structuralist analysis of the Indian caste system, challenging Western assumptions about social stratification. Unlike earlier scholars who likened caste to class-based systems, Dumont argued that caste is a unique form of social organization rooted in a religious and ideological hierarchy, fundamentally tied to Hindu values. He defined caste as a “system of ideas and values” that integrates social, economic, and political relationships through the lens of religious ideology. Drawing on Célestin Bouglé’s earlier work, Dumont identified three core characteristics of the caste system: (1) separation, based on rules governing marriage, contact, and food to maintain ritual purity; (2) interdependence, through a hereditary division of labor where each caste performs specific roles; and (3) hierarchy, a ranking based on the opposition of purity and pollution. Dumont’s concept of hierarchy is central, defined as “a principle of social organization based on the opposition of the pure and impure,” where the pure (e.g., Brahmins) is superior, and the impure (e.g., untouchables) is inferior, necessitating their separation. This ritual hierarchy, he argued, encompasses and subordinates other domains like political power and economic wealth, distinguishing Indian society from Western individualism.

Key Concepts: Purity, Pollution, and Hierarchy

Dumont’s theoretical framework in Homo Hierarchicus hinges on the interrelated concepts of purity, pollution, and hierarchy, which he saw as the ideological bedrock of the caste system. Purity refers to the ritual status associated with proximity to the sacred, most exemplified by Brahmins, who occupy the highest caste due to their role in religious and intellectual life. Pollution, conversely, is associated with activities or states deemed impure, such as contact with bodily substances or certain occupations, relegating groups like untouchables to the lowest rungs. Dumont defined hierarchy as a “system of ranked oppositions” where the pure is superior to the impure, and this opposition structures social relations across all levels of Indian society. Unlike Western egalitarian ideologies, where power and wealth oen define status, Dumont argued that in India, ritual status (purity) encompasses and subordinates political and economic power. For example, the Brahmin’s ritual superiority takes precedence over the king’s temporal power, though the two are interdependent. This “encompassing” nature of hierarchy, where ideology governs social structure, was a radical departure from Marxist or functionalist views that prioritized material or economic factors. Dumont’s insistence on the ideological primacy of purity and pollution drew from classical Hindu texts like the Brahmanas and Dharmashastras, as well as his ethnographic observations, creating a model that was both textual and empirical.

Comparative Sociology: Homo Hierarchicus vs. Homo Aequalis

Beyond his analysis of India, Dumont made significant contributions to comparative sociology by contrasting Indian and Western social systems. In Homo Hierarchicus, he introduced the concept of Homo hierarchicus to describe the Indian social archetype, where individuals are defined by their place in a collective, hierarchical order rooted in religious ideology. In contrast, he later developed the concept of Homo aequalis in works like Essays on Individualism (1983), characterizing Western societies as driven by individualism and egalitarian principles, where personal autonomy and equality supersede collective hierarchy. This binary framework—Homo hierarchicus versus Homo aequalis—highlighted fundamental ideological differences: Indian society prioritizes the collective and ritual status, while Western society emphasizes individual rights and economic power. Dumont argued that these differences stem from distinct value systems, with India’s caste system reflecting a holistic worldview and the West’s individualism reflecting a fragmented, egalitarian one. His comparative approach drew on structuralism, particularly the work of Claude Lévi-Strauss, to analyze societies as systems of meaning. However, critics argued that this dichotomy oversimplified both Indian and Western societies, ignoring internal variations and historical changes.

Methodological Approach: Confluence of Indology and Sociology

Dumont’s methodology, which he described as the “confluence of sociology and Indology,” was a defining feature of his work. He believed that understanding Indian society required integrating ethnographic fieldwork with the study of classical texts. His fieldwork among the Pramalai Kallar and in Uttar Pradesh provided grounded insights into caste practices, while his analysis of Sanskrit texts like the Dharmashastras offered a historical and ideological perspective. This dual approach allowed Dumont to argue that the caste system’s persistence was not merely a social phenomenon but a deeply rooted ideological system sustained by Hindu religious principles. His structuralist lens, influenced by Mauss and Lévi-Strauss, emphasized binary oppositions (e.g., pure/impure) and the encompassing nature of ideology over material conditions. Dumont’s insistence on studying India “from within”—through its own cultural categories—challenged Western sociological frameworks that applied universal models to non-Western societies. However, this approach drew criticism for its perceived overemphasis on ideology at the expense of power dynamics, economic factors, and historical change, with scholars like Nicholas Dirks arguing that Dumont underrepresented the role of political power in shaping caste.

Critiques and Controversies

Dumont’s work, while groundbreaking, has not been without controversy. Critics have challenged Homo Hierarchicus for its perceived rigidity and potential Eurocentrism. Some, like Indian sociologist T.N. Madan, argued that Dumont’s focus on purity and pollution overstated the ideological coherence of the caste system, neglecting regional variations and the lived experiences of lower castes. Others, such as Gloria Raheja, contended that Dumont’s model marginalized the agency of subordinate groups and overlooked alternative principles like gi-giving or power-based hierarchies. Marxist scholars criticized his dismissal of economic factors, arguing that caste was inseparable from material exploitation. Additionally, Dumont’s reliance on classical texts was seen as privileging a Brahminical perspective, potentially reinforcing elite narratives. His comparative framework, particularly the Homo hierarchicus/Homo aequalis dichotomy, was critiqued for oversimplifying Western and Indian societies, ignoring internal diversity and historical evolution. Despite these critiques, Dumont’s work remains influential for its bold theoretical synthesis and its challenge to Western-centric sociological paradigms, prompting ongoing debates about caste, ideology, and comparative sociology.

Legacy and Influence

Louis Dumont’s contributions to sociology endure through his innovative analysis of the caste system and his comparative approach to social theory. Homo Hierarchicus remains a foundational text in Indian sociology, inspiring scholars to grapple with the interplay of ideology, religion, and social structure. His concepts of purity, pollution, and hierarchy have become standard reference points, even among critics who challenge his conclusions. The journal Contributions to Indian Sociology continues to shape South Asian studies, reflecting Dumont’s commitment to interdisciplinary dialogue. His comparative framework, while debated, has influenced cross-cultural studies, encouraging sociologists to consider ideological differences across societies. Dumont’s emphasis on studying societies through their own cultural lenses has also informed postcolonial and subaltern studies, though his work predates these movements. In France, his structuralist approach bridged anthropology and sociology, contributing to the legacy of Mauss and Lévi-Strauss. While his theories are less dominant today due to critiques of their static nature, they remain a touchstone for understanding the complexities of caste and the ideological foundations of social systems.

Conclusion

Louis Dumont’s intellectual legacy is defined by his rigorous analysis of the Indian caste system and his pioneering efforts in comparative sociology. Through Homo Hierarchicus, he introduced a structuralist framework that emphasized the ideological underpinnings of caste, rooted in the concepts of purity, pollution, and hierarchy. His comparative approach, contrasting Homo hierarchicus with Homo aequalis, illuminated fundamental differences between Indian and Western social systems, challenging universalist assumptions in sociology. Despite criticisms of his work’s rigidity and Brahminical bias, Dumont’s integration of Indology and sociology remains a landmark achievement, offering a nuanced perspective on India’s social complexity. His institutional contributions, notably Contributions to Indian Sociology, and his mentorship of scholars further cemented his influence. Dumont’s work continues to provoke debate and inspire research, underscoring the enduring relevance of his insights into the interplay of ideology, culture, and social organization.

References

- Dumont, L. (1970). Homo Hierarchicus: The Caste System and Its Implications (M. Sainsbury, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Original work published 1966)

- Dumont, L. (1983). Essays on Individualism: Modern Ideology in Anthropological Perspective. University of Chicago Press.

- Dumont, L. (1980). Religion, Politics and History in India: Collected Papers. Mouton.

- Pocock, D. F., & Dumont, L. (Eds.). (1957). Contributions to Indian Sociology. Sage Publications.

- Madan, T. N. (1994). Pathways: Approaches to the Study of Society in India. Oxford University Press.

|

© 2026 sociologyguide |

|